|

What Emergency Communication Device Do You Carry?

By David Eden, Rich Stevens, and Nicole Jennings

It is common sense that a paddler's safety kit should include some sort of communication device, absolutely necessary for safe paddling, even in situations that seem entirely close to home on familiar waters in reasonable conditions. From my own experience, calm conditions and sheltered waters can turn very sketchy if a white or black squall suddenly roars through. (Note to self: Don't forget to check the weather forecast before setting out!) This leads to the further question of what sort of device.

Most everybody has a cell phone, so this seems to be a default type. But there are problems. Coverage can be spotty on the water, and the phone should be in some sort of waterproof cover that allows the touch screen to be used and that can be secured in some way to your body. A phone that is kept in a waterproof box in your day hatch or bungied to your foredeck may not be accessible quickly enough, and if you get separated from your boat for any reason, you are out of luck. Attach it to your body because, if attempting to use a cell phone in difficult conditions with wet and cold hands, chances of having it slip away and disappear into 50 fathoms of churning maelstrom are pretty high.

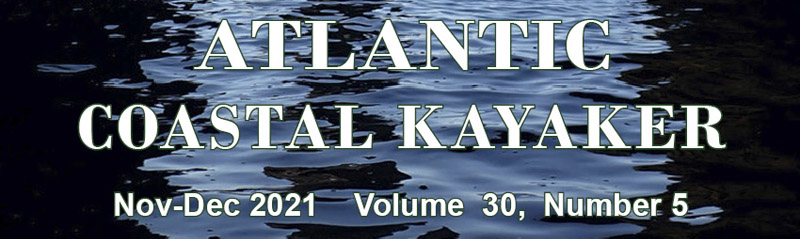

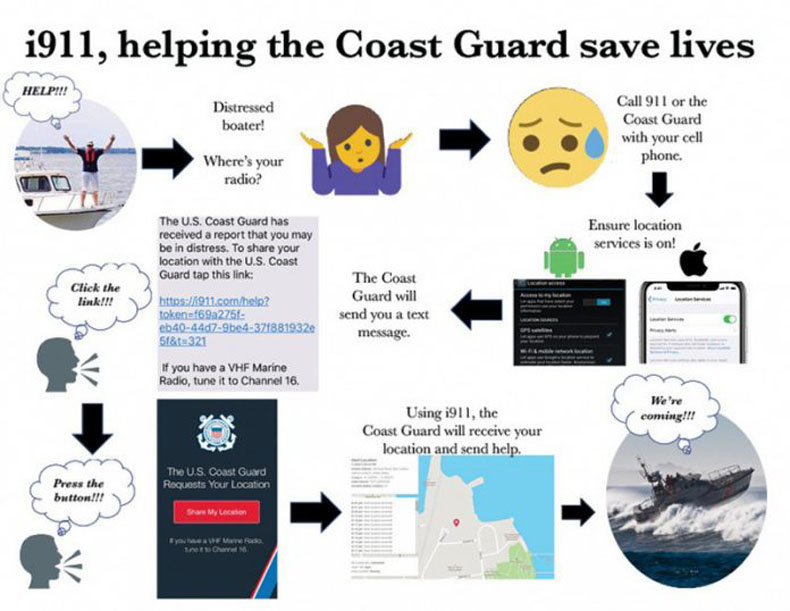

On the other hand, you probably already own a cell phone and know how to use it, so there is an advantage there. You could conceivably call 911 and hope that the call-taker can connect you to an appropriate agency. Better to try and reach the U.S. Coast Guard. Nicole Jennings of MyNorthwest describes the procedure for using a U.S. Coast Guard 911 emergency call procedure, first put online in New England in March of 2020. Note: to use this service, you must have your location on your phone turned on.

The i911 system allows mariners to send their location data with a simple reply to a text message. "It essentially just takes advantage of the proliferation of smartphones, and just how common those are on the water," said Coast Guard Lieutenant Commander Colin Boyle.

Another option in this system is for the mariner to put their number on file with the Coast Guard before going out on the water. If a family member reports the boater has not arrived back at the planned time, the Coast Guard can text the phone number, enabling the missing mariner to share their location data by pressing a button.

"All we need is their cell phone number and if we punch in that number, it will send a text message to that number," he said. "And if they click the button, they start sharing their location with emergency services."

Boyle said it works better than calling, because if phone reception is spotty, sending a text is easier than trying to stay connected for a period of time on a phone call.

There is no need to download an app, and the system works with both Androids and iPhones. It can be used up to 20 nautical miles off-shore.

Boyle said the i911 system has already helped save people in New England, where the technology premiered in March.

"A couple people on an inflatable raft got caught in a current — they weren't planning to be very far off-shore, and they unfortunately found themselves in a situation they didn't plan on," he said. "They luckily had a cell phone, and through that cell phone, the Coast Guard was able to locate them, and a rescue came out to them."

Boyle said the Coast Guard still considers VHF radios the most reliable system of communication on the water, and the new phone technology should not replace radios. Instead, he said, the i911 program is a new "tool for the toolbox."

But notice that last sentence. The VHF radio is still "the most reliable system of communication on the water, and the new phone technology should not replace radios." Of course, if you are paddling on a large lake where the USCG does not patrol, you are limited to your phone or a land-legal device. (It is VERY illegal to use a marine band VHF radio on land, and a lake not patrolled by the USGS counts as "on land.") Alternatives to a VHF radio include a satellite phone, two-meter amateur radio, personal locator beacon (PLB), or a satellite emergency notification device. All of these have significant cons that may make them unsuitable for you.

You can rent a SEND unit, if you don't want to carry the expense of owning one and are planning to be spending some time in the wilds. On our trip down the west branch of the Penobscot River in 2019, trip organizer RICKA Wilderness Chair Chuck Horbert carried one that he had rented for our time in that very remote region of Maine. Outfitters renting gear for paddlers in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area will also rent you a satellite communication device.

Carrying a VHF Radio

A firm believer in having a VHS and attaching it to his body is contributor Rich Stevens, Treasurer of Chesapeake Paddlers Association, Inc..

L: Rich displays the safety gear he wears on his PFD. R: More emergency gear kept quickly accessible.

Rich writes:

ACK ran an article a couple of years back on what people carry in their PFDs and what sorts of safety gear they carry (ACK - June, 2017. Vol. 26 No. 3: "What Do You Wear On Your PFD?"). I was surprised at the number of experienced kayakers who said that they carry their VHF radios on their deck or even in a hatch. I would like to hear people's reasoning on this. There have been a number of stories where people became separated from their boats only to watch as their only means of summoning help sailed off over the horizon without them. Also, if I were in conditions where I needed to summon help, the last thing I would want to have to do is open a hatch.

I consider having a VHF radio close to the importance of wearing a PFD in terms of safety gear. Radios today are small enough and inexpensive enough that there really isn't a good excuse not to have one, especially if you kayak solo or on open water. VHF radios are also invaluable for keeping a large group together. Some trip leaders are now requiring a VHF radio for each paddler on more advanced trips. Here in the Chesapeake Bay area, VHF coverage by the USCG is excellent and more reliable than a cell phone. Many VHF radios also incorporate the NOAA weather channels and have a weather alert function. Very valuable in this area due to common summer afternoon thunder storms that may pop up without warning.

I always have my radio clipped and tethered to my PFD when on the water, regardless of conditions or how familiar I am with the location. While, fortunately I have never needed the radio to summon help for myself, I have used it to summon help for others, as in the case of disabled power boats. I have also used it to summon help at swim supports and report things like fuel spills and hazards on the water. Some people have used a radio to announce taking a group across a busy shipping channel.

In the words of one of our members, "If you don't have it on you, you don't have it."

Basics Steps for Using a VHF Radio

1. Turn on the VHF unit and adjust the squelch by turning the knob until the static stops.

2. Tune to channel 16, the channel monitored by the U.S. Coast Guard. Or use 9.

3. Perform a radio check to ensure your unit is functioning properly—do not use channel 16.

4. Use an "open channel" to performance the check (channels 68, 69, 71, 72 and 78A).

5. Turn radio to one-watt power setting, and key the microphone.

6. Call "radio check" three times, followed by your boat name and location.

7. Wait for a reply confirming someone has heard your transmission.

8. For general communications, always use channel 16.

Using a VHF Radio in an Emergency

Tune the radio the channel 16 and full power.

If there is a danger to life, transmit "Mayday Mayday Mayday" and your vessel name. You can call yourself "Kayak," plus boat type or your own name, eg "Kayak Necky," "Kayak Arluk," "Kayak Josephine."

Wait for the Coast Guard to respond and be ready to reply with your location, ideally with latitude and longitude from GPS.

If your situation is bad but not life-threatening, use the call "pan-pan."

To see a detailed discussion of how to use a VHF radio, visit Paddling Light. The post also includes a list of several radio brands with links.

PLB vs. Satellite Messenger (SEND)

I am going to let the experts cover this topic. Outdoor School Instructor Lindsay McIntosh-Tolle of REI, Portland, Ore., covers the topic in her article," How to Choose Between a PLB and a Satellite Messenger" one of the REI Expert Advice pages.

Other Methods of Signalling

There are a number of ways to signal distress if there is there is a potential rescuer in sight or hearing. The universal request for assistance could be three blasts on a whistle or air horn, three gunshots or three flashes of a light in succession followed by a one-minute pause and repeat until acknowledged. A small emergency airhorn can easily fit into a PFD pocket and probably has a greater range than a whistle. (See ACK Vol 24 No. 2, April 2015 for a discussion of whistles and their limitations).

You could carry a lightweight signalling mirror, with a hole for attaching a lanyard. These presuppose sunlight to work well. Be sure to get one that has the directions written on the back.

A flashlight may be useful at night, but a powerful light is too heavy for kayakers and a small one is far too dim to use in the day and may not even be strong enought to attract anyone's attention at night. Besides there is always the issue of corrosion to deal with.

A flare pistol or small flares might also be a useful item, but again there are issues of corrosion and flares also need to be replaced periodically. You could carry a blank pistol for loud signalling, but you are going to use up a lot of blanks if you have to keep up the signalling for a while.

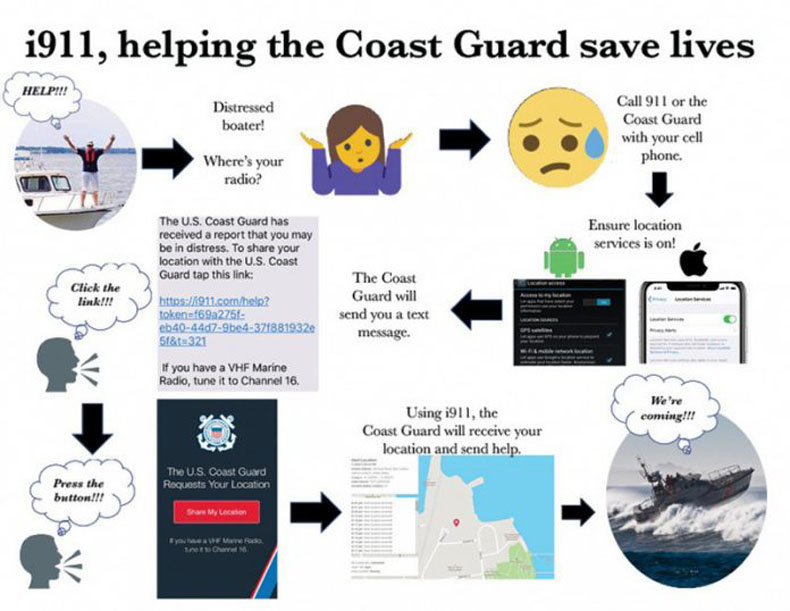

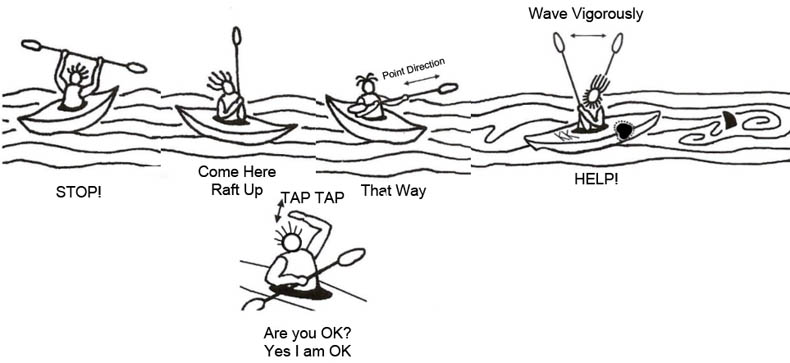

If you are in a group and can see each other, you could use the common paddle signals to communicate. This supposes you are with other paddler who periodically visually check each other out.

Image courtesy of Kelowna Canoe and Kayak Club (KCKC).

A possible solution for communication within a group is to use two-way radios. These are NOT suitable for calling the Coast Guard, but can be used for talking to fellow paddlers. I worked for a guide company that used these on day trips. They seldom worked very well, and the company stopped using them. A higher quality unit that also floats and is waterproof like the one shown might be acceptable. The one shown is an example only. This is not an endorsement, by any means. It is important to check all the reviews before deciding to buy.

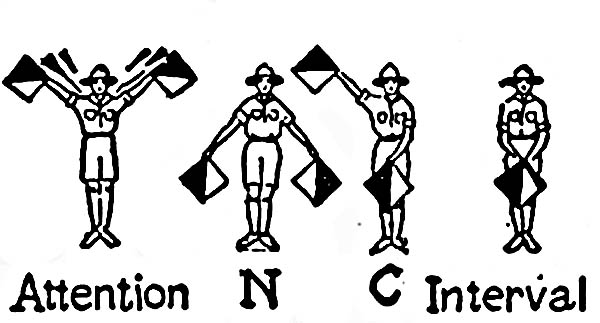

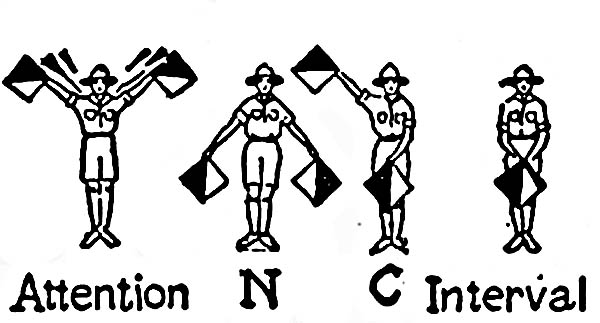

None of these solutions appeal to you? Well, you can always use semaphores.

In the International Code of Signals, "NC" means "I am in distress and require immediate assistance."

|