|

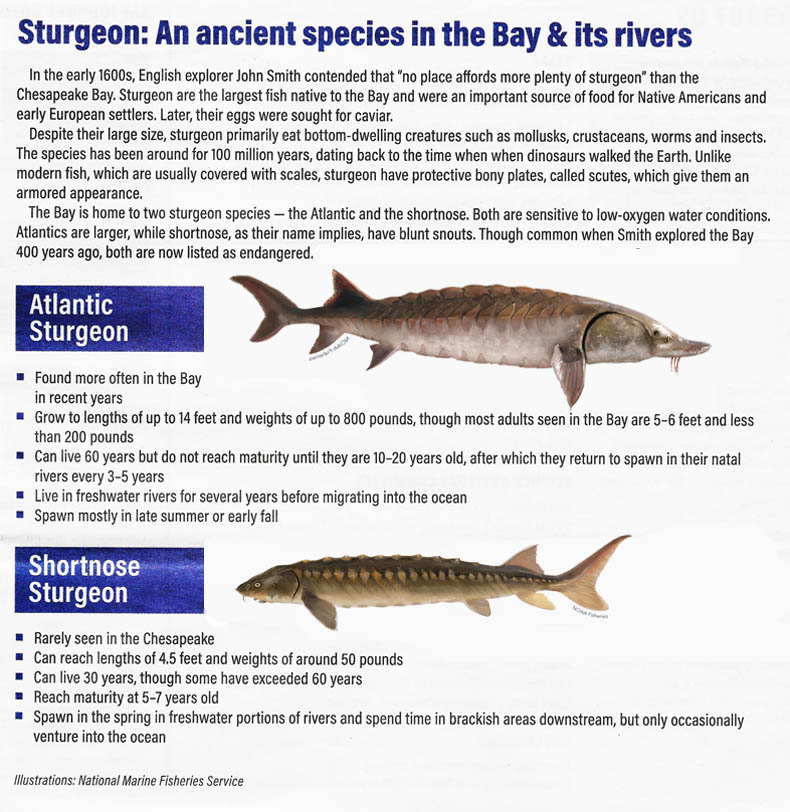

During that time, 1,590 Atlantic sturgeon turned up, but just 93 shortnose sturgeon — even though the shortnose spend most of their lives in the freshwater rivers where they spawn and in nearby brackish water. Atlantics, in contrast, spend most of their lives in the ocean after spawning in rivers.

While some of the shortnose were found in the Potomac, most were captured north of the Bay Bridge. That has contributed to speculation that many, if not all, shortnose seen in the Bay in recent decades are migrants — not Chesapeake natives — who have come into the Bay from the adjacent Delaware Bay through the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal.

A 2009 paper studying DNA collected from shortnose along the East Coast found that samples from within the Chesapeake showed that the fish appeared to have originated in Delaware Bay.

"In the Delaware, there's a healthy spawning population," said Mike Mangold, a biologist with the Fish and Wildlife Service who tracks sturgeon reports along the East Coast. "It could be they might out-migrate and are colonizing a new area."

Such colonization might be necessary if, in fact, any remnant native population in the Bay has vanished, as the genetic works suggests.

Still, it's also possible that shortnose sturgeon are simply being overlooked. Marty Gary, executive director of the Potomac River Fisheries Commission, said that he hears reports from commercial fishermen that shortnose occasionally turn up in their nets, but they "have some trepidation" about reporting catches of an endangered species because they worry it could trigger restrictions.

For his part, Cohn, who caught the sturgeon in DC, said he viewed the catch as tangible evidence that the river was improving. A native of the District, Cohn worked at Fletchers when he was young and volunteers to help address pollution problems in the river.

"It just really made me hopeful for the upward trend of the health of the river and all that goes with that," Cohn said.

The Potomac Conservancy's most recent grade of the river's health last year was a B- which, although a slight drop from the group's previous report card, still reflected a "river on the mend" from a legacy of industrial and agricultural pollution decades ago. As recently as 2011, the group had given the river a D.

"Thirty to forty years ago if you jumped in the Potomac you would be getting a tetanus shot if you were within sight of downtown," Cohn said. "Now we got shortnose sturgeon hanging out. It seems like the water quality is dramatically improved."

Editor David Eden found this dead baby Atlantic sturgeon while paddling on the Hudson River south of West Point. 1974.

|