Farthest North — The Sledge and Kayak Journey South

By Fridtjof Nansen. Illustrations from the books.

Introductory notes by David Eden

One of the greatest dreams of European explorers over many centuries is to extend our knowledge of geography ever farther north. From the Greek explorer Pytheas of Massalia (modern Marseilles) through Christopher Columbus and into the 19th century C.E., intrepid sailors and adventurers have faced extreme cold, ice, and the unknown in their attempts to push the boundaries.

Often these explorers were not inspired by the pursuit of scientific knowledge alone, but by commercial or nationalistic motives. The experiences of the former, the fishers after whales, walruses, and seals, formed the basis of the practical knowledge necessary to face the rigors of the arctic in wooden sailing ships.

Wooden sailing ships had two ways of dealing with the sea and pack ice that challenged them. They could either hope to avoid it completely or, accepting the inevitability of becoming frozen in, as with a whaler that had stayed too long on the fishing grounds, try to develop ways to survive the experience. That this was often a failure was shown by the fates of the Franklin expedition in 1847 in Victoria Strait, northern Canada; the U.S. western whale fleet off northern Alaska in late 1871; and the loss of the USS Jeanette off the northern coast of Siberia in 1881.

It was that last loss that is of significance to this tale. Wreckage from the Jeanette was discovered three years after the tragedy near the eastern coast of Greenland, hundreds of miles from where the ship was crushed in the ice. That discovery indicated an east to west current of the pack ice. And this is where Fridtjof Nansen comes in.

Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen was a scientist and explorer who was already lionized for his feat of accomplishing the first crossing of Greenland, an endeavor which had been scorned by many as sure suicide, especially since he had planned to do it on skis with a minimal crew, only six men. He came to believe that by taking advantage of the arctic drift, a properly-designed ship could cause itself to be frozen in the ice and possibly be carried across the Arctic Basin over the North Pole itself. While the desire to gain the farthest north record was part of the nationalistic "Race to the Pole" of the late 19th century, Nansen also planned a years-long program of oceanographic and meteorological studies as part of the expedition. Nansen's idea was met with derision and he had some trouble raising funds.

The Fram departs, July, 1893.

Nonetheless, Nansen had a vessel, the Fram, specially designed and built to withstand the pressures of the pack ice. The Fram left Christiana, Norway, on June 24, 1893, turning north and east to sail along the northern coast of Europe and Siberia. Just west of the New Siberian Islands archipelago, the Fram turned north again and wedged itself in to the drift pack in September, 1893.

For the next 18 months, the Fram drifted slowly and erratically westward. It became clear that she was not fated to drift over the Pole, so in March, 1895, Nansen put into practice a new plan: When the ship reached 83° N, Nansen and crewman Hjalmar Johansen would make a dash for the Pole using dog sledges and skis (or "snowshoes," as the crew referred to them), while the Fram, under the command of Otto Sverdrup, would continue its drift westward. (The ship finished the experimental drift and returned to Norway in August, 1896, just a few days after Nansen and Johansen made it back.)

The Fram frozen in, summer, 1894. Note the "snowshoes" and the windmill for auxiliary power.

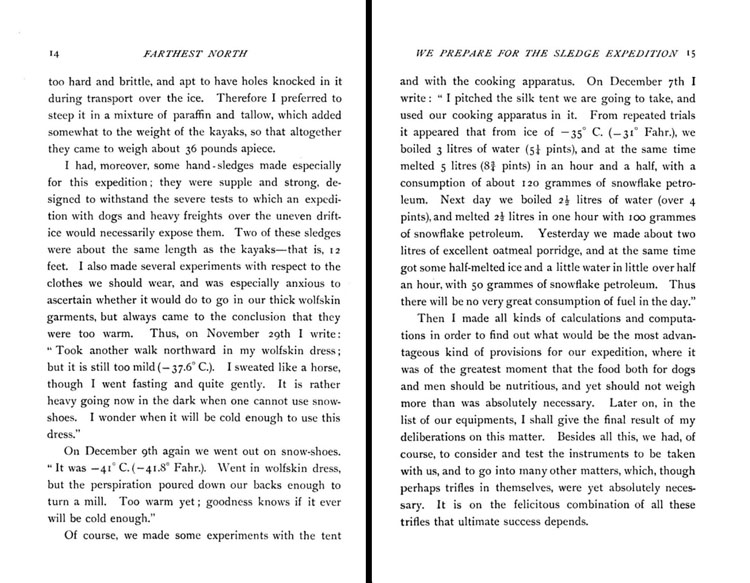

Nansen was 410 miles from the Pole when he started out. Among the equipment he brought on the journey were two kayaks that he had made from bamboo and canvas that would be needed to ferry them across open leads in the pack ice as well as entirely open water on their return trip

While the pair made better time that they had calculated, they were moving against a southwards movement of the pack ice, so that it soon became clear that they would have to turn back before reaching the Pole or not have sufficient supplies to reach safety. Finally, they encountered a seemingly endless field of impassible, broken ice and were forced to turn south. They had set a new northerly record of 86° 13.6' N before they began their retreat.

I was lucky to find the original two-volume record of Nansen's popular telling of his adventures in our local library. (Unfortunately, the library shortly afterwards disposed of all its 19th volumes.) Still, I was able to find facsimiles of the books online. Over the next several issues, I will be presenting Nansen's incredible tale of his retreat southwards on skis and in kayaks, using the facsimile pages,

These are not the chronicles of an egotistical macho man bragging about his accomplishments. Nansen a strong streak of romanticism and uncertainty in his writing. Anyone who has read Thor Heyerdahl's popularizations of his adventures will recognize this tendency. Such delicacy of temperment may be unexpected in two such intrepid scientist/adventurers, but perhaps it is a prerequisite for the motivations of these two Norwegian adventurers, separated by 60 years.

|

Nansen chooses his companion for the sledge and kayak trip and does some fretting.

Nansen describes the kayaks and other aspects of the preparations.

Excellent oatmeal porridge?

Preparations for the race to the Pole continue.

|