A Channel Islands Tour

By Kevin Mansell. Photos by Kevin Mansell.

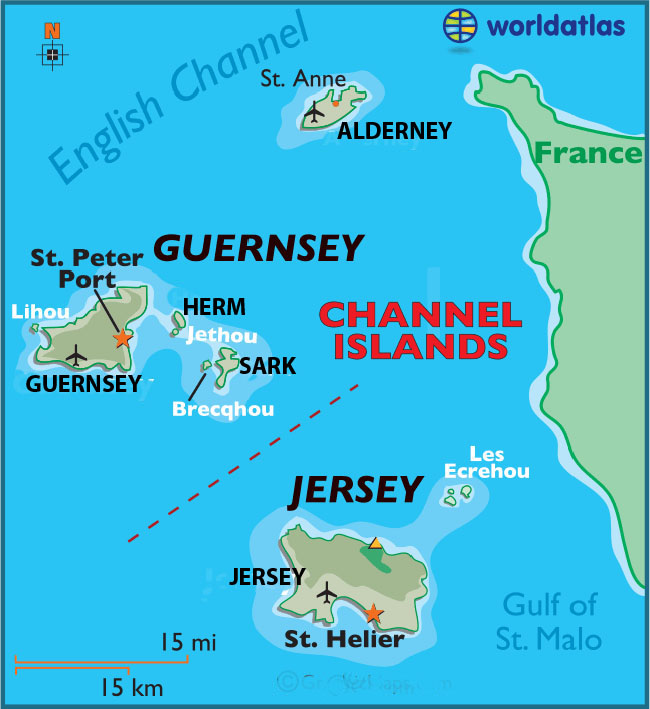

Mention the Channel Islands to most North American kayakers and their thoughts probably turn to an archipelago off the Californian coast, but what about the original Channel Islands? Located off the coast of northern France, they sit between the arms of Normandy and Brittany, a unique mixture of English and French culture. (Considered the remnants of the Duchy of Normandy, they consist of two Crown dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey; and the Bailiwick of Guernsey, consisting of Guernsey, Alderney, Sark, and some smaller islands. - Ed)

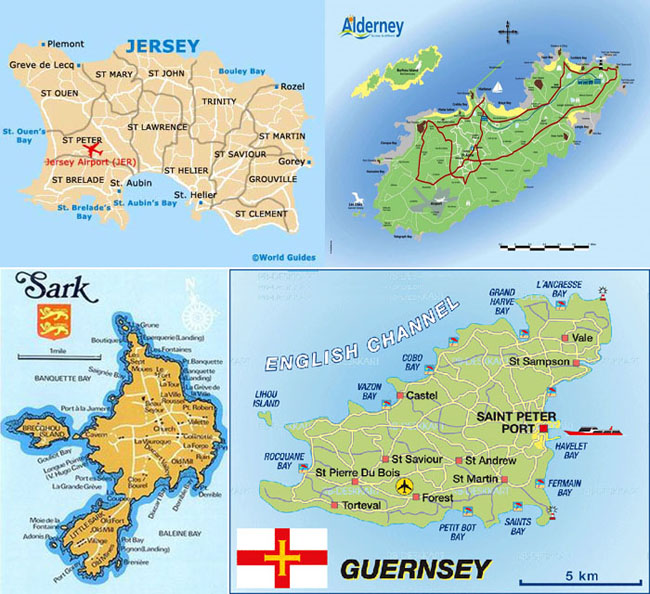

Jersey, the largest, is my island home. Large is a relative term, as it is only nine miles long and five miles wide. Within this compact 45 square miles, there is some dramatic coastal scenery set against a rich historical background, which stretches back approximately 240,000 years. The kayaking is made all the more interesting by the twice daily rise and fall of the tide, with a tidal range which reaches 12 meters (39 feet) on the larger spring tides.

My paddling organization, the Jersey Canoe Club, was formed in 1974. Back then, "canoe" was a generic term for anything that was paddled; today we paddle almost exclusively sea kayaks. Members of the Club developed their skills and gained experience in local waters before moving further afield in search of paddling challenges. One area which the members visit regularly is the west coast of Greenland, so regularly in fact that the Club has eight sea kayaks based in Ilulissat, on Disko Bay.

This summer, though, some of us from the Club looked for paddling adventures in our own backyard. No loading kit into North Face holdalls and struggling through international airports. It was a simple matter of driving four miles from home, unloading the kayak and heading out for eight days. A pretty minimal environmental carbon impact.

L: The view from the inside of one of the larger caves on Sark. R: Pausing for a swim at Eperquerie, one of the earliest landing places on the island. A cannon in the foreground is used as mooring post for small boats.

Fog rolling in along the west coast of Sark. A warning of what was to come a couple of days later.

Our first destination was Sark, just over 12 nautical miles to the north. Our departure was timed to coincide with the start of the northerly tidal streams. In the Channel Islands, it's a matter of working with the tides, otherwise failure and epic paddles are the potential outcomes. A quick radio call to the Jersey Coastguard and soon we were heading north at five knots. We have a good working relationship with the local coastguard, always radioing a passage plan when we are heading offshore. It is reassuring to hear a friendly voice on Channel 82.

The crossing, to Sark took two hours and 50 minutes in almost perfect conditions, and before lunch we were lifting the kayaks up the beach before heading to the campsite. Sark is a unique island, retaining many attributes of a feudal society. No cars are allowed on Sark. The island was settled from Jersey in 1565. Elizabeth I gave permission for 40 families to settle there, in an attempt to discourage French pirates. Each house had to be able to supply a man with a musket for the island's defence.

We walked up the hill to the campsite before setting off in search of a place to swim and a restaurant. The pattern for the week was paddle a few hours, put up a tent, and eat out. Its surprising how much room there is in a sea kayak when you don't have to carry a weeks worth of food.

Sark was to be our home for two nights, as we planned to paddle around the Island, the following day. Even exploring the bays, the total distance of a circumnavigation is only eight nautical miles, but it took us seven hours to complete. There is just so much to see, endless caves, stacks, and arches, including one long tunnel which has currents pouring through reaching speeds of five knots.

Creux Harbour, on the east coast, was the original sheltered landing, built in the 1860's. We stopped off there for coffee and cake while waiting to meet Jim, who was paddling up from Jersey. The weather was unseasonably hot , so we needed to refresh ourselves on a regular basis by swimming in the crystal-clear waters. After leaving Creux Harbour, we stopped at L'Eperquerie landing on the island's northeast, one of the earliest anchorages on the island, where the small boat mooring bollards are re-cycled upside-down cannons, salvaged from the shipwreck of the East Indiaman ship, Valentine.

The west coast of Sark provided plenty of amusement and some challenges as thick fog obscured part of the route. The tidal streams were heading south with us as we threaded our way through the offshore reefs, great entertainment, and seven hours after we left Dixcart Bay, we were lifting the kayaks back up the beach.

L: La Coupee, the narrow neck of land which joins Little Sark to the larger section of Sark. R: Looking west from Pilcher Monument. The large island in the distance is Guernsey. The white sands of Shell Beach on Herm can just be made out. That would be our lunch spot the following day.

The following day we headed to Herm, a particularly small Channel Island, with a resident population of 60, swelled during the summer months by seasonal workers for the tourist industry. Only just over three nautical miles from Sark, timing was of the essence, as we had cross tides running up to four knots at time. With correct planning the crossing was really easy and before long we were sitting on Shell Beach, on the northeast coast of Herm, a beach reminiscent of the Caribbean as opposed to northwest Europe. A celebratory swim was in order as the particularly warm weather continued.

Nicky paddling past Brecqhou, a private island with no landing allowed. The tide is running north and some movement can be seen, but we were on neaps so it was manageable.

L: Approaching Shell Beach on Herm. It's hard to believe that we are in the British Isles. R: Perfect conditions approaching Herm.

Herm has a fascinating history and is lovingly cared for by the people who live and work on the island. The campsite is close to the highest point on the island, offering superb views of not only where we had paddled from but our proposed route for the following morning. Our destination was Alderney, the most northerly and isolated of the Channel Islands. We were looking at a 22 nautical mile day, 17 of which were going to be an open crossing.

Those days spent working out vectors on a British Canoeing "Open Water Navigation and Tidal Planning Courses" were going to pay off. If conditions deteriorated on the crossing, we could miss Alderney; among other factors, we had to plan for tides reaching five knots in strength, and these were only neap tides! It's one thing to be able to plan the navigation in a classroom with time and resources on your side. It's a different situation when you are sitting in a field, with limited resources and a restaurant booking fast approaching.

Fortunately, Janet was pretty quick with the calculations and soon we were heading down the path towards the restaurant. One of the pleasures about kayaking in the Channel Islands is the possibility of eating out in a variety of quality restaurants. This is not a wilderness area, but a populated archipelago, but with some really high-quality kayaking, which requires careful tidal planning.

The following morning, I radioed into Guernsey Coastguard, informing them that eight sea kayakers were leaving Herm for Alderney, with an estimated time on the water of just over five hours. The forecast was perfect, apart from the hint of some mist patches. As we headed north through the reef to the start of the crossing the hint of mist turned into the reality of thick fog. Visibility was well below 200 meters.

L: An interesting navigational mark. A six-knot speed limit to avoid disturbing the puffins. R: Leaving Herm early in the morning. I had just radioed the Guernsey Coast Guard and was pleased with the weather conditions.

As we sat contemplating our next move the coastguard called for our position and our intentions. It should only be a mist patch, so we decided to press on in the hope that the forecast was correct. The Coastguard seemed surprised by our decision and insisted that we radio in every 30 minutes with our location, the visibility, and most strangely the welfare of the group, a request that I had never had before.

As we headed into the fog we quickly settled into a rhythm, senses tuned into any unusual noises and aware of a building two-meter swell. I radioed in after 30 minutes and again after an hour. I missed off the welfare report on the second radio call and the Coastguard was immediately back on the radio requesting information on the condition of the group. It would have been so easy to have been flippant and answer that one person had a sore shoulder, another person was feeling slightly menopausal, etc., but I resisted the temptation. What was an issue though, was that out of 60 minutes potential kayaking time, 15 minutes had been spent on the radio.

The forecast mist patch evolved into an 18-mile-wide, dense fog bank, so we were within a few hundred meters of Alderney before we eventually saw the vague shape of its cliffs looming out of the fog. It was a pretty good test of the accuracy of our navigation, without doubt satisfying to those who had drawn the vectors the night before.

30 minutes later the fog had surrounded us and it stayed that way for nearly five hours. A good test of navigational planning.

Alderney appearing from the fog. Seeing the cliffs bought a sense of relief.

Alderney is the closest of the Channel Islands to both France and England, with a turbulent past. This is reflected in the numerous fortifications dotted around the coast. Possibly the darkest period in the history of the island was during the Second World War, when the island was evacuated prior to being occupied by the forces of Nazi Germany. The fortifications and anti-tank walls can be seen all around the island plus the memorials to the foreign slave workers who died as a result of the appalling treatment they received.

Thankfully, today Alderney is a much happier place and we enjoyed a couple of peaceful days exploring the northern isle. It was also with some relief that we watched the fog disperse prior to our paddle south back to Sark and eventually Jersey. It was a late afternoon departure from Alderney, we had a 22 nautical mile paddle, of which, 18 were an open crossing, but we had tide and visibility on our side. Five hours after leaving and just as the sun set on another superb day, we pulled ashore in Dixcart Bay, Sark, 60 hours after we had left on our crossing to Herm.

Kate passing Fort Houmet Herbe, completed in 1854 it is one of numerous military fortifications around the coastline of Alderney.

L: The daily ritual of eating in a restaurant. A very civilised way of undertaking an eight-day sea kayaking trip. R: Alderney Lighthouse on Quenard Point. It was built in 1912 to warn ships of the treacherous waters around the island. In March, 2011, the powerful light was replaced by much weaker lights. Previously it could be seen from 23 nautical miles away but the powerful beam was replaced by a couple of LED lights which can only be seen from 12 miles away.

Angus leaving the southern tip of Alderney, its about 17 nautical miles to our next landing. Conditions were ideal.

Arriving in Sark. We took a day to explore the island on foot before heading back to Jersey on our final 12 mile crossing.

One thing many of us are guilty of is the desire to travel the world in search of paddling adventures. We graze on a diet of Instagram feeds, magazine articles, etc., drawn to ever more remote and exotic locations, while we neglect those areas close to home. We should be thinking about exploring in detail our local environment, gaining an intimate knowledge of the history, geography, and wildlife of our home area.

We are fortunate living in Jersey, in that distances are small. We only drove ten miles in total, to enable this paddle to take place: Eight days of superb kayaking and, for most people on the trip, new places to visit, especially Alderney, which isn't paddled to that often.

Alastair Humphreys* has developed the concept of microadventures, they should be short, simple local, and cheap, opening up the world of adventure to people who otherwise might not have access to challenges in the outdoors. Our trip at the end of July certainly met most of the criteria of a microadventure, although we could perhaps have eaten in cheaper restaurants at times.

To Get To Jersey

Ferries

From G.B., about a ten-hour trip without much savings in price.

Manche Iles Express

Condor Ferries

Airlines

British Airways from London's Gatwick is

probably the easiest.

Flybe. Air

easyJet: www.easyjet.com

Clubs and Outfitters

The Jersey Canoe Club welcomes visiting kayakers. They have kayaks for use and members who are eager to share the local waters with visiting kayakers.

Gorey Watersports

Absolute Adventures

Kayak Adventures

Jersey Adventures

|

Kevin Mansell: Although born in England, Kevin grew up on Jersey, an island he has called home since the mid 1960s. Kevin spent his working life as a school teacher. Kayaking has been an integral part of his life since he was given his first kayak in 1969. He has earned his A BC Level 5 Coach and has spent years exploring remote areas of the world, with his favorite areas being the west coast of Greenland and Baja. Retirement in 2016 has allowed him to spend even more time on the water. You can read about his kayaking journeys at www.seapaddler.co.uk.

|

*Alastair Humphreys does have a website, alastairhumphreys.com, but I received an error message from Firefox when I tried to access it, including the following warning:

"It's likely the website's certificate is expired, which prevents Firefox from connecting securely. If you visit this site, attackers could try to steal information like your passwords, emails, or credit card details."