It has been said that in the Northeast, you can experience five seasons in the space of an hour: spring, summer, fall, winter, and biblical. That was certainly the case this past weekend (April 5-6) when we had rain, blizzard whiteout, dense fog, sleet, frozen rain, high winds, and warm sunny conditions all within 24, if not a single hour.

This is the shoulder season, in which we have to dress for water temperatures that are still well below the cold-water shock level, while risking heat stroke as the temperature in the drysuit rises to something around sauna levels. Red maple buds are returning to the trees; the sociable rafts of loons that visit our coast are abandoning their winter congregations and heading back to their long summer solitudes and the travail of chick-rearing; red buds on the maples signal sugaring time; and we are already pulling ticks off the dog.

Soon deep spring will be here, with its clouds of black flies, and summer with its suffocating plethora of biting, sucking, and stinging insect life. Here in our home port of Ipswich, Mass., when the vicious greenheads come out in July and the worst of the black fly infestation farther north and west is over, my thoughts again to the clear and abundant waters of the Adirondacks.

Ever since a childhood camp experience on the shore of Lake George, I have had a special feeling for the lakes and rivers of northern New York state. I have paddled, puddled, skated on, skied over, swum in, and hiked along the lakes, rivers, and creeks that nourish and drain the area. In 1974, I hiked, rafted, and kayaked the length of the Hudson River from its highest source, Lake Tear in the Clouds, on the shoulder of Tahawus, the Cloud Splitter (rather mundanely known by its official moniker of Mt. Marcy), along Opalescent Creek, all the way from the mountains to the sea, where its waters mix with and disappear into the Atlantic; but its bed continues to the edge of the continental shelf as the mighty Hudson Canyon.

On the other side of Tahawus from Lake Tear, Johns Brook rushes down into Keene Valley, at one point, three miles from the trailhead, forming one of the great swimming holes of the Adirondacks, rushing over smooth, potholed rock slabs in a series of slides, basins, and deep pools surrounded by plenty of sun-warmed stone perfect for alternately baking and quick cooling on a hot summer afternoon with the complimentary scents of dusty fir-scented forest and mountain water freshening the nose.

Keene Valley has a place in my family history, as well, for it was here that my many times-great grandfather (my namesake) settled after fleeing the armies of British and native Americans heading south under Burgoyne. My not-so-many times great-grandfather wrote down this bit of family lore many years later, as well as recounting his own experience of being chained to a tree with a supply of a few days food while his father surveyed the surrounding forests. I have, myself, walked the same trails and drunk from the same streams and even paddled where great-great-great-great-great Grandpa did, for these are the headwaters of the Hudson, and they are in places nearly as pristine as they were in his day.

Almost pristine implies a certain amount of development, and there is plenty enough of that in the Adirondack Park. This incredibly complex patchwork of state and private land constitutes one of the oldest and largest parks in the country. Development has gone on with few restrictions in the private portions of the park. Wealthy magnates in the 19th century built vast private estates as part of their own commercial interests, including a number of dams that now dot the region; this has actually been a boon to paddlers, as it means there are many dozens of miles of flatwater paddling on lakes that once were rivers.

About the time the aforementioned David Ward was growing up in the Adirondacks (in the 1820s and 30s), another young man was also maturing in what was still the relatively wild northeast, developing a love for “roughing it” that would stay with him throughout his life. He would later become one of the most beguiling of the siren calls tempting the public into the glorious Adirondacks.

Everyone who remembers with delight the traditional ways of the woods, whose nostrils tingle with the smell of canvas tents and Old Woodsman bug dope, who remember the rough but warm texture of wet wool redolent of wood smoke knows of George Washington Sears, writing as “Nessmuk,” and his book Woodcraft and Camping, first printed in 1886 and still in print nearly a century later, one of the first handbooks of the wild to come out for an audience personally separated from wilderness life, but longing for the experience as the primeval forest became more and more remote from daily experience. (If you are interested in reading this wonderful old book, you can access a facsimile of the original and download it for free from the website for the Gutenburg Project’s website: www.gutenberg.org/files/34607/34607-h/34607-h.htm.) Filled with all the reader would need to know about camping, hunting, fishing, camp cookery, and canoeing. In all, but most notably in the case of paddling, he was an early proponent of traveling as light as possible, a philosophy that has become easier to hold to in this day of super light materials. Why Nessmuk became an apostle of camping with extreme simplicity in the golden age of the Adirondack guide boat, beautifully handcrafted but weighing in far closer to 100 pounds than the incredibly lightweight 10-12 pound canoes he used, is another story.

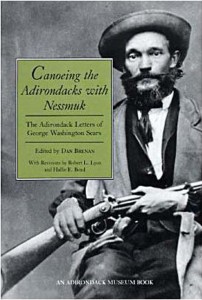

Fortunately for posterity, Sears chronicled his adventures in the Adirondacks in a series of letters to Forest and Stream, letters which have been collected and reprinted in one volume, available in many bookstores and on the web:

Canoeing the Adirondacks with Nessmuck

Canoeing the Adirondacks with Nessmuck

Edited by Dan Brenan, with revisions

by Robert L. Lyon and Hallie E. Bond

Format: Paperback,177 pages

Publisher: Syracuse University Press

Publish Date: March 1993

ISBN-13: 9780815625940

ISBN-10: 0815625944

Ret: $12.24 (walmart.com)

This little volume is a must read for anyone who wants to know more about paddling in the Adirondacks. One often thinks that stories about travelling in the wild from the 19th century, especially about areas that have been built up

Sears was not a large man, nor was he particularly healthy. Unlike the common image of the outdoorsman as a Paul Bunyon or Dan’l Boone, larger than life, eating a stack of pancakes ten feet tall, Sears stood just a few inches over five feet and weighed only 110 pounds. Also, by the time he was exploring the Adirondacks, he was experiencing health problems from recurring malaria and possibly tuberculosis picked up during an adventurous life that included a trip as a sperm whaler, long treks through the eastern wilderness, and even a journey to Brazil and up the Amazon to explore the possibility of making a fortune in the rubber industry.

So when Sears came to the Adirondacks, which were characterized by many portages, some exceeding ten miles, he had planned to travel as lightly as possible, not merely because he did not want to burden himself with a guide. (Sears was too poor to pay the $2.50 daily wage of a guide, and preferred travelling alone.) He was an old man by the standards of the age, weakened by disease, and he simply couldn’t carry heavy gear around. So he began a search for the lightest craft he could find. Working with boatbuilder J.H. Rushton, he paddled a series of cedar, clinker-built, increasingly tiny craft that culminated in the Rushton, an incredible eight-and-a-half feet long, 23 inches broad, with a depth of eight inches and weighing just one ounce under ten pounds. Sears only used this craft in protected waters in Florida. The last Rushton boat he paddled in the Adirondacks, the Sairy Gamp, was not much bigger, with dimensions of nine feet by 26 inches, six inches deep, and ten-and-a-half pounds.

Sears’ descriptions of his travels in the light boats caused a rush of orders for similar craft. Rushton complained, “Every damned fool who weighs less than 300 thinks he can use such a canoe too. I get letters asking if the Bucktail (slightly larger than the Sairy) will carry two good-sized men and camp duffel and be steady enough to stand up in and shoot out of.”

Even back in the 1880s the Adirondacks had lost their wildness in many areas. During Sears’ paddling summer of 1881, he travelled down the Fulton chain of lakes, portaging 3/4 of a mile from Fifth to Sixth lake, where the influence of a new dam was seen. Sears wrote,”The shoreline of trees stood dead and dying, while the smell of decaying vegetable matter was sickening. Last season, Sixth Lake was a wild, gamy place, and the best of the chain for floating. Its glory has departed…The present season finds the forest of balsam, spruce, and hemlock converted into a dismal swamp of dying trees, foul, discolored waters, and fouler smells.”

Despite his occasional despair at the despoilation of the wilderness, Nessmuk’s book is a wonderful glimpse into a world of lusty woodsmen and guides, city dwellers and pulmonary sufferers seeking refreshment in the wild, colorful backwoods characters, and glorious fishing and hunting. I strongly recommend this book.

Author Archives: kaiyaque

A Rising Tide Floats All Boats

- Marsh grass off the northeastern end of Hog (recently renamed Choate) Island.

It is glorious to paddle in the fall “spring tides.” I went out recently three days after the new moon. The marsh was flooded like an inland sea, at 12 feet, unlike the usual nine to ten feet. Instead of having to follow channels, you point your bow and shoot over to the landmark you wish to reach, floating over ditches, boardwalks, marsh, and salt pans. The other advantage is a bigger window of time in which you paddle – three hours on either side of high tide in my case before it’s mud.

Here is a technical description of these unusually high fall tides: “Approximately twice a month, around new moon and full moon when the Sun, Moon and Earth form a line (a condition known as syzygy) the tidal force due to the Sun reinforces that due to the Moon. The tide’s range is then at its maximum: this is called the spring tide, or just springs. It is not named after the season but, like that word, derives from the meaning “jump, burst forth, rise”, as in a natural spring.

The colors are glorious today: the tawny gold of marsh grass, the crinkley maroon of the faded sea lavendar, the bright pink glasswort (better than the New England maple trees in fall!). Wildlife has flown south. Gone are the kingfishers, the yellow legs, the Great egrets. The Great blue heron is one of the last to go. Black ducks fly up and away startled, honking madly. The light breeze rustles the phragmites reeds. On this afternoon, the duck hunter has brought out provisions to his cabin on the inland sea for the upcoming hunting season. He sits on the porch soaking up the sun with his dog.

Unusual high tides will occur at the new moon around the 15th of the month for the next few months. See you on the water and happy fall paddling.

– Tamsin Venn

Fall Paddle by Tamsin Venn

How did fall get around back here so quickly? Here I am making my annual autumnal trip around Hog Island, drawn by the huge fall tides of 11 feet flooding the marshes for a few days. Everything is on the move. Three great blue herons rise to get away from me, and land farther on. A dozen great egrets poke around for minnows. A sure sign of fall, the kingfisher drops down from low branches chattering away, the ducks pinned on a fog-smudged sky. The seagulls wheel down and up. Straight clear light peels out of the pine trees; the emblematic reminder of colonial falls, the Choate House sits in solitude on the edge of the island, much as it did in the 17th century. The cormorant appears much bigger than its middling size. All a satisfying feast for the senses, as the snowbirds prepare to fly south.

Welcome to the ACK blog site

As a seed to our new blog site, I have posted the editorial from our most recent issue, June, 2012.:

Despite the thousands of images of happy families cheerily paddling across calm and pristine water, we must always be aware that danger and disaster are constant companions of kayakers, be they lake or ocean paddlers, neophyte or expert. A moment’s miscalculation, minutes or even seconds of lapsed awareness, can cause a pleasant excursion to end in extreme discomfort, injury, or even death.

The causes are manifold. A botched roll, an unexpected change in the weather, a miscalculation of a group’s capabilities, forgetting an essential piece of equipment can all lead to disaster. And once the calamity occurs, survivors often find that their private sorrow becomes a public debate, their actions generating a ruthless spate of reportage, analysis, criticism, and even mockery. The degree of publicity, once limited to the reach of local media, has spread widely with the ever-increasing use of the world-wide web. People can now join debates on accidents and disasters that take place on the other side of the world, within hours or minutes, or even as the event is occurring.

The burden this communicative ability places on the families and friends of victims must be extreme. We have all seen and deplored the reporter thrusting a microphone in the face of family and friends who are still shocked and horrified at their tragedy. How much harsher must it feel when discussion continues long after the tragedy, and starts to condemn the victim for hisown death or injury. How much is too much probing? Where do the rights of the survivors for privacy supercede the public’s right to know, the journalist’s mandate to inform, and the expert’s responsibility to educate?

These questions have come up many times in many places, and there does not seem to be any agreement on them. We came across the debate again during research into a recent kayaking death off the coast of Scarborough, Maine. We will follow the story as it developed over a few weeks to illustrate how information spreads and how it ended. More info is in the Safety department of this issue.

The story at first was fairly bare-bone. On April 14, 2012, the body of a man, late returning from a kayaking trip, had been found after an extended search a half-mile offshore. He was face up, wearing a wet suit and a PFD. His kayak was found in the surf at a local beach. He was an experienced kayaker. The story was posted on line on the local paper’s website. Despite the paucity of information, comments immediately began to be posted, some inane, some speculative, and some very defensive. The latter were mostly from family and friends asking for discussion to end. Others were from people angered by the commentary and speculation as to cause of death. While none of the commentary struck us as derogatory, many did criticize the dead man for injudicious behavior.

Later articles began to paint a very different picture. The victim had just recently purchased his boat and had only kayaking once before. This was his first ocean trip. The kayak was ocean-capable, but the man was paddling solo to an exposed island nearly a mile and a third out. When he started, visibility was very good, air temperature was in the 50s and winds were low. The water was extremely cold, in the low 40s. He reached the island around 10:43 in the morning.It is not known when he left. He was reported missing in the late afternoon, and his body was found around 7 P.M. The light winds had risen to 17 mph, gusting to 20 or 25 mph (from different weather channels) in the afternoon and the calm seas had risen into two to four foot swells, becoming ever rougher as the day progressed, a common situation in the area. His wet suit provided only minimal protection against cold under the circumstances. According to newspaper reports, his death was later attributed to accidental drowning.

It is fairly clear that the boater in question had tried to prepare himself according to his knowledge, but that his knowledge and therefore his preparation were inadequate. He did tell people where he was going and when he was expecting to return. He called a friend from a sandbar to tell him to expect him to dinner. On a poignant note, he even posted pictures to his Facebook page once he reached his destination celebrating his paddle. Even so, he went poorly prepared and engaged in needlessly reckless behavior with an almost arrogant disregard for the dangers and for the risks to which he was putting himself and thus his family and friends. A friend was quoted after his death as saying his behavior indicated a positive capacity, a tendency to “jump in with both feet.” Is a cautious assessment of risk an indication of lugubrious gingerliness, of too much circumspection? A disregard for danger is often seen as a dashing and positive attribute, but a person who maximizes a concern for safety can have as much fun, while being more likely to return in one piece. We have personally driven to the emergency room with people who leaped before they looked.

Once a person dies under public circumstances, his death becomes public property. If the death is caused by the activities of the victim, it can be certain that all aspects of the death will be discussed in public forums.

We in the kayaking community know that every accidental kayaking death can be a matter for seemingly endless speculation and theorizing. With the advent of newspaper pages posted on the web with the public able to post comments, the debate has expanded into the larger community. This can be very painful to family and friends who choose to visit such sites.

The commentary on this person’s death ranged from the idiotic (“A kayak has no business on the ocean!”) to the desperate (“Please stop the commentary. This man was a friend.”) And yet those who admire a friend’s derring-do have to be prepared for the burden of his accidental maiming or death. All of us who engage in activities that can be dangerous have to be prepared for disaster, and one way to prepare is to analyze disasters that occur. Unfortunately, the very public nature of the discussion allows both brainless blather as well as reasoned assessment. Even the blather can be useful, as it demonstrates one way in which the non-participating public views a person’s sport. This discussion will and must go on, and cannot be considered “disrespectful” (from another comment). The lessons learned from the mistakes of one man can save the lives of many others, and those who have friends killed taking risks, as we have, must be prepared for the burden of public commentary.