If you’re like us, your net bag contains many items that may or may not be useful for that day’s paddle, but you keep everything in there just to cover your bases. But, whenever you’re getting ready to go paddling, there are a handful of things you can do and bring to make your trip safer and more fun. Watch this video to see a simple checklist that every experienced kayaker runs through every time and you should too, say ACA-certified sea kayak instructors Paul and Kate Kuthe. Thanks to paddling.com for letting us know about this useful reminder series.

Author Archives: kaiyaque

Paddle Florida Trips Announced for 2018-19 Season

Paddle Florida’s line-up for next season is posted now and registration is open. Here is a great opportunity to paddle some of Florida’s most scenic waters in good company. Click on trip links at Paddle Florida for more details on each event. New next season is the Flori-Bama Expedition on the Perido River. Forming the border between Alabama and Florida, this stream meanders past extensive woodlands of pine, cypress, and juniper cedar with many sandbars along the journey to Perdido Bay and barrier islands in the Gulf of Mexico. The ever popular Florida Keys Challenge will be making a come-back next season in an altered form which will showcase beautiful Bahia Honda State Park and surrounding islands. Rivers, springs, lakes, coastal waters – Paddle Florida will explore them all next season! Sign up soon if you’re interested. Registration opened June 1, and some trips fill quickly.

Upcoming Trips

Suwannee River Wilderness Trail

October 19-24, 2018

Celebrate Florida’s version of autumn on its most famous river. The trip spans 65 miles of the scenic Suwannee and a portion of the (northern) Withlacoochee, from Madison Blue Spring to Branford. This section features dozens of clear blue springs perfect for swimming and snorkeling.

Register by: October 5

Flagler Coastal Wildlife Experience

November 1-4, 2018

Paddle with dolphins, meet rescued sea turtles, and float by historic forts as you immerse yourself in the rich cultural history and natural beauty of Florida’s northeast coast.

Register by: October 18

Ocklawaha Odyssey

Nov 30-Dec 4, 2018

Float over Florida’s most famed first magnitude spring and see monkeys dangling from cypress branches, a rich diversity of birds, while exploring an Old Florida land- and waterscape on this 48-mile paddle down the Silver and Ocklawaha Rivers.

Register by: November 16

Wild, Wonderful Withlacoochee

January 17-22, 2019

Beginning at Lake Panasoffkee, paddlers will thread their way through hardwood swamps and tannic streams on a 60-mile journey to the Gulf of Mexico. The adventure includes a side trip to the colorful Rainbow River and its world class first magnitude spring.

Register by: January 4

Florida Keys Challenge

February 9-15, 2019

Paddle the azure coastal waters of the Middle Florida Keys, including the length of the famed 7-Mile Bridge, explore mangrove tunnels, and watch sea turtle surface beside your kayak, and enjoy a snorkeling trip out to Looe Key.

Register by: January 26

Flori-Bama Expedition on the Perdido River

March 10-15, 2019

Paddling the Florida/Alabama border, enjoy beach camping along a cozy meandering river to the more open waters of Perdido Bay as we explore the most diverse set of ecosystems of the season.

Register by: February 24

Suwannee River Paddling Festival

April 5-7, 2019

With camping atop the bluff overlooking two beautiful rivers, our season-capping festival takes place at Suwannee River State Park near Live Oak. The weekend will offer supported 8-12 mile paddling options on both the Suwannee and Withlacoochee Rivers, a concert featuring Paddle Florida’s favorite musicians, and educational presentations from regional waterway experts.

Register by: March 22

Today is the 30th Anniversary of the Maine Island Trail

Today is the 30th anniversary of the Maine Island Trail — the day in 1988 when 12 citizens met to form the Maine Island Trail Association and create “an outstanding waterway for small boats” along the coast of Maine. Since then, more than 33,000 coastal explorers and stewards have helped ensure that over 200 wild islands on the Trail remain pristine and accessible.

The Maine Island Trail is a grassroots effort launched by citizens seeking to visit and steward the wild, uninhabited islands of Maine. While friends groups exist for many public parks, there are few if any others where a simple handshake agreement between 100 disparate landowners and thousands of users and volunteers has created a nationally known recreational entity.

The idea of a coastal water trail in Maine was born in the late 1970s following a land survey conducted by the State of Maine of the uninhabited coastal islands. The survey determined that the State held title to some 1,300 unclaimed islands, rocks, ledges, and low-water bars along the coast. In the mid-1980s, the State collaborated with the Island Institute, a nonprofit organization serving the islands and communities of the Gulf of Maine, to evaluate the recreational potential of these properties. As part of this evaluation, Dave Getchell, Sr., a founder of MITA, explored the length of the coast and identified some 40 public islands suitable for recreational use. These public properties eventually formed the nucleus of the original Maine Island Trail.

In the fall of 1987, Dave declared in an editorial column in Small Boat Journal that “In studying this bounty [of islands], it occurred to me that here was a rare chance to develop an outstanding waterway for small boats that would use the state-owned islands for overnight stops, similar to the way hikers use pathways like the Appalachian Trail.” This was the inception of what recreational boaters today call a water trail – a concept replicated over 500 times in North America.

In that same editorial, Dave asked readers who were interested in the concept to write him and attend a meeting to discuss it. Twelve people attended the initial meeting. Amusingly, that first assembly felt sufficient determination to establish a member numbering system, drawing lots for those first dozen member numbers. (That numbering system operated continuously until 2013 when it exceeded 25,000 and required a new database, but many of MITA’s founders can proudly tell you their member number to this day.)

During this early contemplation of the Maine Island Trail, a concern was expressed that widespread and unchecked visitation could damage the natural integrity of the fragile coastal islands. Dave therefore wrote a proposal to the Maine Bureau of Parks & Lands and L.L.Bean for modest seed money to create a “Maine Island Trail Association” that would be charged with caring for the trail islands to ensure the integrity of their wilderness character. The proposal was funded, establishing a partnership between the Island Institute and the Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands that L.L.Bean has supported ever since. The Maine Island Trail Association (soon dubbed MITA) was now official.

With the Trail’s growing popularity, MITA’s significance grew, as did its divergence from the core mission of the Island Institute. In a difficult decision, MITA became an independent nonprofit entity in 1993. It moved its office from Rockland to the Portland waterfront and gradually grew to a staff of eight. Among other innovations, it partnered with Rising Tide Brewing Company to launch an award-winning beer (Maine Island Trail Ale) in 2013 and with Chimani to launch a very successful smartphone app in 2014.

The Trail itself has steadily grown to encompass the entire coast of Maine – from New Hampshire to Canada – and to include well over 200 islands and mainland sites. Island owners recognize that MITA’s simple handshake deal works: through a set of stewardship programs, MITA and its members keep Trail islands in better physical shape than they would be if left off the Trail. And while the original Trail islands were public property, private islands were soon added and eventually eclipsed the number of public islands. By 2010, the most frequent additions to the Trail came from private land trusts.

Thirty years old in 2018, the Maine Island Trail has been dubbed by National Geographic one of the “50 Best American Adventures.“ With over 5,700 active members, MITA is the largest water trail association in North America and a model for other trails across the country.

Watch this video featuring Dave Getchell, founder of the trail: https://vimeo.com/240724482

Lake Tanganyika

I’m proud to report that I’ve completed the second lake on my African trifecta, Lake Tanganyika. Lake Tanganyika is the longest lake in the world, the second largest by volume, the second deepest, and is known for its diversity of fish species.

Before I go on about this leg of the expedition, I’d like to give an update on expedition ethics. When I came up with the idea of this trip, I decided that I wanted to do it in the best style possible. To me, that meant solo, human powered, and without a support team. I intended to carry all of my equipment along with me, resulting in no reliance on others – truly unsupported.

Before I go on about this leg of the expedition, I’d like to give an update on expedition ethics. When I came up with the idea of this trip, I decided that I wanted to do it in the best style possible. To me, that meant solo, human powered, and without a support team. I intended to carry all of my equipment along with me, resulting in no reliance on others – truly unsupported.

Unfortunately, I found that the weight of my equipment made it impossible to bicycle between lakes considering the topography along my route. So, begrudgingly, I made the decision to send the kayak ahead to Lake Tanganyika where I met up with it after about a week of bicycling. I’m still going strong on the other aspects that I am striving for: solo, human powered, and without a support team. But I can’t claim entirely unsupported anymore. Perhaps someone will come along in the future and improve on my style.

I started Lake Tanganyika at Kasanga, near the Tanzanian border with Zambia. From there, the lake stretches out as far as you can see to the north. It’s rather narrow there though, so you can see across to Zambia and the DRC.

The southern portion of the lake, between Kasanga and Kipili is extraordinarily beautiful. The lake is deep, with clear, blue water and a dramatic shoreline of mountains and large boulders – many larger than a house. With the exception of one day, the weather was calm and I made good time of about 25 miles a day.

This area is not very populated, so I split my time between “bush” camping on wild beaches and staying in small fishing villages. Staying in the fishing villages was a similar experience to Lake Malawi, except that very few people in this region speak English, so communication was more difficult.

With the benefit of having experienced two full lakes, I can confidently say that this southern section, as well as Mahale Mountain National Park, are the most beautiful paddling segments so far. I think that any paddler would find Kasanga to Kipili to be extraordinarily rewarding, and worthy of consideration as a world class sea kayaking destination.

With the benefit of having experienced two full lakes, I can confidently say that this southern section, as well as Mahale Mountain National Park, are the most beautiful paddling segments so far. I think that any paddler would find Kasanga to Kipili to be extraordinarily rewarding, and worthy of consideration as a world class sea kayaking destination.

This section ended at Lake Shore Lodge in Kipili. It’s a really cool place that must feel like the end of the Earth to most guests arriving there, but to me it felt more like going back into civilization. The two South African owners, Louise and Chris, hosted me and provided luxuries that I had grown unaccustomed to on the water. They have vast experience on the lake, including long sea kayaking trips and a fleet of boats (even equipped with a compressor for SCUBA), so I greatly enjoyed sharing my experiences with them and soliciting as much advice as possible.

I headed out from Kipili feeling good, and completely unaware of the challenge that I was going to face.

If you had asked me before this lake what I was most concerned about, I would’ve probably said crocodiles or hippos or maybe getting sick in such a remote area. As it turns out, something called Rukuga was going to be my biggest obstacle.

That first day out of Kipili, I enjoyed calm weather until late afternoon. At that point, a strong north wind started blowing and I headed to a beach to see if it would stop. After about an hour, I decided to spend the night there. The beach was only about 10 feet wide and before a steep sand bank went up about another ten feet. I set up my tent up on the bank, but something seemed ominous about my boat below, so I decided that I needed to bring it up also.

This wasn’t so easy because I’m paddling a tandem Long Haul Folding Kayak – a capable, but not light, boat. What I ended up doing was flipping it several times, basically rolling it up the hill. It worked, and I made dinner and went to bed.

In the night, an extremely powerful storm came through. It was one of those storms that pulls the tent stakes out of the ground immediately and makes you sit up and brace the tent for fear that the poles will snap.

In the morning, much to my surprise, the beach below was completely gone and there were only jagged rocks present. The waves from the storm has pounded the beach and removed all of the sand. The lake itself seemed angry, with serious wind chop and about a 15 knot north wind. Still, I felt that it would likely pass by midday and I might as well head out.

I paddled north and made very poor progress due to the north wind. It formed rolling waves of 6-9 feet and required power to overcome. In 10 hours of paddling, I managed a measly 19 miles. That certainly didn’t match the effort that I had expended.

I stopped in a village for the night. Here, I was actually able to connect to the Internet and look at the weather forecast. It’s hard to explain how it felt to see that the forecast called for 10-15 knot north winds for at least the next week. It seemed that there was a point, basically the northern terminus of Mahale Mountain National Park, where a west wind from the Congo would split north and south. It was about 100 miles away, and I didn’t see any alternative to just forcing my way through it, as unappealing as that seemed. I certainly couldn’t wait for a week and hope that it would stop.

I’d later find out that this wind is called Rukuga, and it’s a seasonal north wind that brings rain. It usually only lasts 2-3 days, but occasionally lasts longer. In this case, it seemed like I’d need to pass it myself rather than wait for it to end.

The next few days were difficult. I’d paddle for about 10 hours and only manage 17-20 miles a day. The topography of the shoreline didn’t give me much shelter, and because of the strength of the wind, I was forced to paddle consistently for fear of being blown backwards and losing ground.

Eventually, I made it to where the land mass juts out into the lake and forms Mahale Mountain National Park. I planned on paddling around a point and then camping just outside the southern boundary of the park. From there, I’d have to cover 30 miles on the following day to make it to a lodge, Greystoke Camp, where I would spend the night. Although I had been averaging under 20 miles a day, I was still hopeful that I could make it to Greystoke in one day. This was especially true because Mahale has a large hippo and crocodile population and poor beaches for landing and camping safely.

As I paddled out to the point, I was still heading into the wind. I wasn’t sure if it was wrapping around the land, or truly blowing from the west, but when I turned the corner it was extremely rough and the wind was blowing furiously from the north. Although the waves were close to 10 feet, they were rolling waves and weren’t dangerous to me, but I quickly realized that I couldn’t make progress in those conditions so I turned back around for the shelter of the point.

I went back out twice more, but found that the conditions hadn’t improved and realized that I would need to camp there for the night. This was a low point, as I was 6 miles south of the park boundary and certainly 36 miles made Greystoke out of reach. I assumed that I’d need two days of struggling against headwinds to make it to camp, which meant a night alone in the National Park.

In the morning I paddled out and, shockingly, found a south wind! By 1230, I reached the best looking landing site from the satellite maps and had to make a decision – stop here for the day or push on to Greystoke. If I went forward, I probably had to make it because it didn’t seem like there were any other good places to pull out in the next 15 miles.

But it was only 12:30, and despite an uneasy feeling that the wind would turn, I headed north. Amazingly, the wind did not turn, and after a week of brutal north winds, on the day that I really needed help, the winds completely changed direction and helped me paddle my new one day record, 36 miles.

Mahale Mountain National Park is an incredible landscape of several thousand foot mountains, covered in thick tropical jungle, abruptly falling down into the blue lake below. When I was paddling south of Greystoke, I started to hear this loud series of noises emanating from the forest above. There was no question what it was: a community of chimpanzees were warning about my presence.

Mahale Mountain National Park is an incredible landscape of several thousand foot mountains, covered in thick tropical jungle, abruptly falling down into the blue lake below. When I was paddling south of Greystoke, I started to hear this loud series of noises emanating from the forest above. There was no question what it was: a community of chimpanzees were warning about my presence.

Arriving at Greystoke was such a remarkable feeling. I felt proud to arrived there in the manner that I had and so grateful for their warm welcome. Greystoke is a remote, luxury camp which rivals any camp in Africa. It’s only accessible by water and air, and has direct access to semi-habituated communities of chimpanzees.

The architecture of the main building immediately signaled what this place was like: open air, constructed of natural and local materials, but exquisite and immaculate. That night I had dinner with the other guests and the managers, Fabio and Barbara, and regaled them stories of my current expedition, as well as some older classics. I told my Amazon pirate story, as I do whenever it seems marginally relevant. I went to sleep happy.

The company and hospitality of everyone at Greystoke, the creature comforts of the camp, and the knowledge that I had made it to within a stone’s throw of the dividing line of the Rukuga wind, only a few miles to my north, had resulted in a foundational change in my attitude. My faith that I would succeed on this lake was renewed.

The next day was a blur of pleasure. I went out and observed a group of chimpanzees, 14 in total including multiple babies. Although Mahale Mountain National Park’s sister park, Gombe Stream National Park is perhaps more famous due to the fact that it was the location of Jane Goodall’s work, Mahale is larger, wilder, and contains many times more chimpanzees. It has also hosted researchers since the 1960s. This has resulted in communities of semi-habituated chimpanzees that will allow you to observe them at close range without aggression. At times, I was within a few feet of them. Without overly anthropomorphizing our close relatives, they really did seem to have interesting, human like behaviors. At times there were disputes within the group and they would make noises and scatter. Then they would draw back in to a tighter unit. Mothers cared for the babies, who played and explored. It was magical.

The next day was a blur of pleasure. I went out and observed a group of chimpanzees, 14 in total including multiple babies. Although Mahale Mountain National Park’s sister park, Gombe Stream National Park is perhaps more famous due to the fact that it was the location of Jane Goodall’s work, Mahale is larger, wilder, and contains many times more chimpanzees. It has also hosted researchers since the 1960s. This has resulted in communities of semi-habituated chimpanzees that will allow you to observe them at close range without aggression. At times, I was within a few feet of them. Without overly anthropomorphizing our close relatives, they really did seem to have interesting, human like behaviors. At times there were disputes within the group and they would make noises and scatter. Then they would draw back in to a tighter unit. Mothers cared for the babies, who played and explored. It was magical.

The next morning I was of course sad to go, but my psyche was entirely different than it had been before Mahale and Greystoke. I enthusiastically paddled north out of the park and towards my last scheduled stop on the lake: The Nature Conservancy’s (TNC) Tuungane Project office in Buhingu.

In Buhingu, I met with TNC resident experts who were working at the Buhingu office. They graciously allowed me to spend 2 nights there, and observe some of the work that they were doing. Just by chance, I was there during a training session of people from the different communities. Each of the 16 villages had sent their two best people to be trained on climate smart agriculture by their instructor, Apollinaire Williams. In the morning there was a classroom session, and in the afternoon we went out to the field, where Apollinaire instructed them on how to collect field data, identify suitable agricultural areas, and appropriate planning for sustainable agriculture. I think that TNC is unique in that it has the capacity and expertise to train people to contribute to the project.

After that, I went and met with Jeremiah Daffa, who is the Governance and Gender Officer at the Buhingu office. We attended a practice of the Mahale Youth Drummer Group, who have been organized under the Tuungane Project’s “model household” initiative. The members of the group were educated on family planning, gender equity, and environmental sustainability, and then they have written their own songs which they perform in different villages to educate other people. Jeremiah’s other work include initiatives to prevent early pregnancies, address the problem of girls not reaching secondary school, preventing the production of bush charcoal (a job predominantly carried out by women), and working to make sure that there are beneficial relationships between the Tuungane Project and other stakeholder, partner, and related organizations, such as the local, regional, and national governments, Pathfinder International, the Jane Goodall Institute, and the Frankfurt Zoological Society.

Again, I left there in high spirits. The Tuungane is doing good work, and their Population, Health, and Environment approach to conservation has me very optimistic about the region.

The remaining portion of the lake was unremarkable. The weather was good and I was able to make swift progress, paddling 75 miles in my final 2 days. I did start to meet Congolese and Burundian people, who had come to Tanzania to escape the turmoil of their own countries. The population closer to Kigoma is larger and the lake is more obviously impacted.

I reached Kigoma, the most remote large town in Tanzania, about 3 weeks after I set out from Kasanga. Despite the challenges, my time on Tanganyika was incredibly special, and I urge others to go visit. It’s world class.

Right now I’m biking between Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria, and I’ll check back in with updates soon.

Paddling the African Great Lakes: North End of Lake Malawi

I finished Lake Malawi and have moved on to Tanzania. I believe that my last check in was around Nkhata Bay, before I headed into the rugged and beautiful Viphya Mountain section of the lake. This area is incredibly beautiful, with mountains that drop a few thousand feet down to the lake and then extend more than 2,000 feet down underwater. It’s the deepest part of the lake and the water is clear and cool and a beautiful azure. Along this section, there are few beaches – the shoreline is mostly rocky. It’s also nice because the deep water and rocky shoreline mean that there are no crocodiles, hippos, or schistosoma.

The one challenge is that this area often experiences higher winds. The water can be quite rough and headwinds can be quite challenging. The typical routine was to keep my head down and paddle into a strong headwind from around 6 am to 12 or 1 pm, at which time the wind would calm down and I could enjoy the remaining afternoon of relative ease.

I think that this section, paddles over four to five days with a few rest days to hike and snorkel shows tremendous opportunity for a sea kayaking destination. The tourism would certainly benefit the local economy.

While I do feel a bit robbed of the wilderness experience of paddling the Mozambique/Tanzania side of the lake, it was quite rewarding for me to stay on the Malawi side where people speak English and I was able to freely communicate with the local people and learn about the lake and how they live.

Almost all of the people are dependent on the lake and the land around it for subsistence fishing and agriculture. Unfortunately, their practices are not sustainable, so I worry about the future of the lake without education and enforcement of fishing regulations. It’s a classic tragedy of the commons situation, where people are struggling to get by and therefore are taking as much of the available resources from the lake and land as they can. Almost half of the population is under 14, so the population is growing quickly and these problems will just be exacerbated.

Still, the people of Malawi were consistently kind and welcoming to me, and I really think that has earned its reputation as the “Warm Heart of Africa.”

My next lake will be Lake Tanganyika, the longest lake in the world and second largest by volume. It will also be considerably more remote than Lake Malawi, and there will be the added challenge of people only speaking Swahili. I’m looking forward to the challenge and wild beauty of the region though, and I’ll plan on updating you on my progress.

Here are some photos from the lake. The one of the stars is fishermen using lights to attract Lake Malawi sardines, called usipa. This nightly phenomenon prompted David Livingstone to dub Lake Malawi, the Lake of Stars.

I’d also like to add that my kayak continues to perform admirably. I found it to be consistently stable, durable, sporting an impressive payload, and fast considering all of those other factors. The boat is really adding to my confidence heading out into these lakes alone. Upon breaking down the boat at the end of the lake, I wasn’t able to find any wear or damage. Not bad for three weeks paddling in Africa!

Paddling the African Lakes: Lake Malawi

Jan. 26. The trip is going well so far. A few days have been derailed by weather, but otherwise I’ve been making steady progress. I decided to paddle the Malawi side instead of the Mozambique side as they speak English on this side and I thought it would be interesting to be able to talk to people and hear about the lake and their lives firsthand. For the rest of the trip, virtually everyone will speak Swahili.

I’ve been following a routine of waking up around 5 and paddling until mid afternoon and then usually staying in small fishing villages at night. The people along the lake have been very kind and welcoming. They’re fascinated by all of my stuff, but especially the boat. They use dugout canoes, so my kayak is pretty shocking to them. My boat has been awesome, very stable, pretty fast considering I’m solo paddling a tandem and it’s loaded with a ton of cargo, and it easily fits all of my equipment. No issues whatsoever so far – the boat is helping a lot with my optimism and high spirits.

There haven’t been any mishaps yet. The only thing that’s a bit unsettling was that at one point I was paddling about 400 yards off the opening of a big lagoon, and I heard some sloshing in the water. I turned and saw a big crocodile about 20 yards away. It was at least 12 feet long and looking right at me. I definitely set a new personal speed record in the following minutes.

I planned the trip for 20 miles a day, and so far that seems pretty reasonable. My best day so far was 31 miles and my worst was 18, with a strong headwind. I’m sure that mileage will go up as the trip goes on and my fitness improves.

I have a few more days on this section, and then I’ll get to my first planned break – Nkhata bay. I’ll probably just be there for one1 rest day, but from there it kind of feels like the home stretch. From Nkhata Bay, I have about six more days of paddling and then this lake is in the bag and it’s on to bicycling towards Tanzania.

It’s been interesting to see the people along the lake, how they fish, and some of the environmental impacts. The lake is clear and blue except near rivers, where deforestation has caused huge amounts of sediment to turn the lake a muddy brown. The local people fish both using nets and lines with hooks. Some people are beach seining, which is pretty destructive. Others go out at night, far offshore, and use lights to attract the fish. It’s cool to look out on the lake at night and see dozens of lights in the distance.

I’m feeling good and confident. This lake should go down without too much of a fuss.

Paddling the African Great Lakes: TNC

Tuungane Dugout, Lake Tanganykia. Photo courtesy of The Nature Conservancy

Tuungane Dugout, Lake Tanganykia. Photo courtesy of The Nature Conservancy

January 5, 2018 Update

By Ross Exler

I first became aware of the African Great Lakes while I was a student working in the Alexander Cruz lab at the University of Colorado. The lab’s research was focused on novel species of fish endemic to Lake Tanganyika. Working with these species introduced me to the biodiversity of the African Great Lakes, but also the threats to the continued survival of these ecosystems. I soon realized that the African Great Lakes region is globally significant to biodiversity, vital in sustaining the lives of the millions of people who call the region home, but also tragically suffers from a comparatively low profile to conservation efforts in other regions. Therefore, a founding element of this trip was to find and support a non-profit whose work in the region aligned with my conservation ethos.

So, when I had adequately planned my trip, I conducted some research on the leading conservation groups active in the region, and found that The Nature Conservancy has a large scale project, the Tuungane Project, on Lake Tanganyika. The Tuungane Project brings a multidisciplinary approach to conservation and addressing the extreme poverty that is the underpinning of environmental degradation in the region. Their efforts are introducing fisheries education and management, terrestrial conservation, healthcare and women’s health services and education, agricultural training, and other efforts to increase the quality of life and understanding on how human activities impact the very resources that the local people depend on for survival. Without the buy in of local communities, efforts to conserve this incredible region will likely be unsuccessful.

I am happy to announce that I will be working with The Nature Conservancy to promote greater awareness of the value and threats to the region, as well as their conservation initiatives on Lake Tanganyika. If you have some time, please visit the Tuungane Project website and read more about the great work that they are doing.

https://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/africa/wherewework/tuungane-project.xml

Paddling the African Great Lakes

By Tamsin Venn

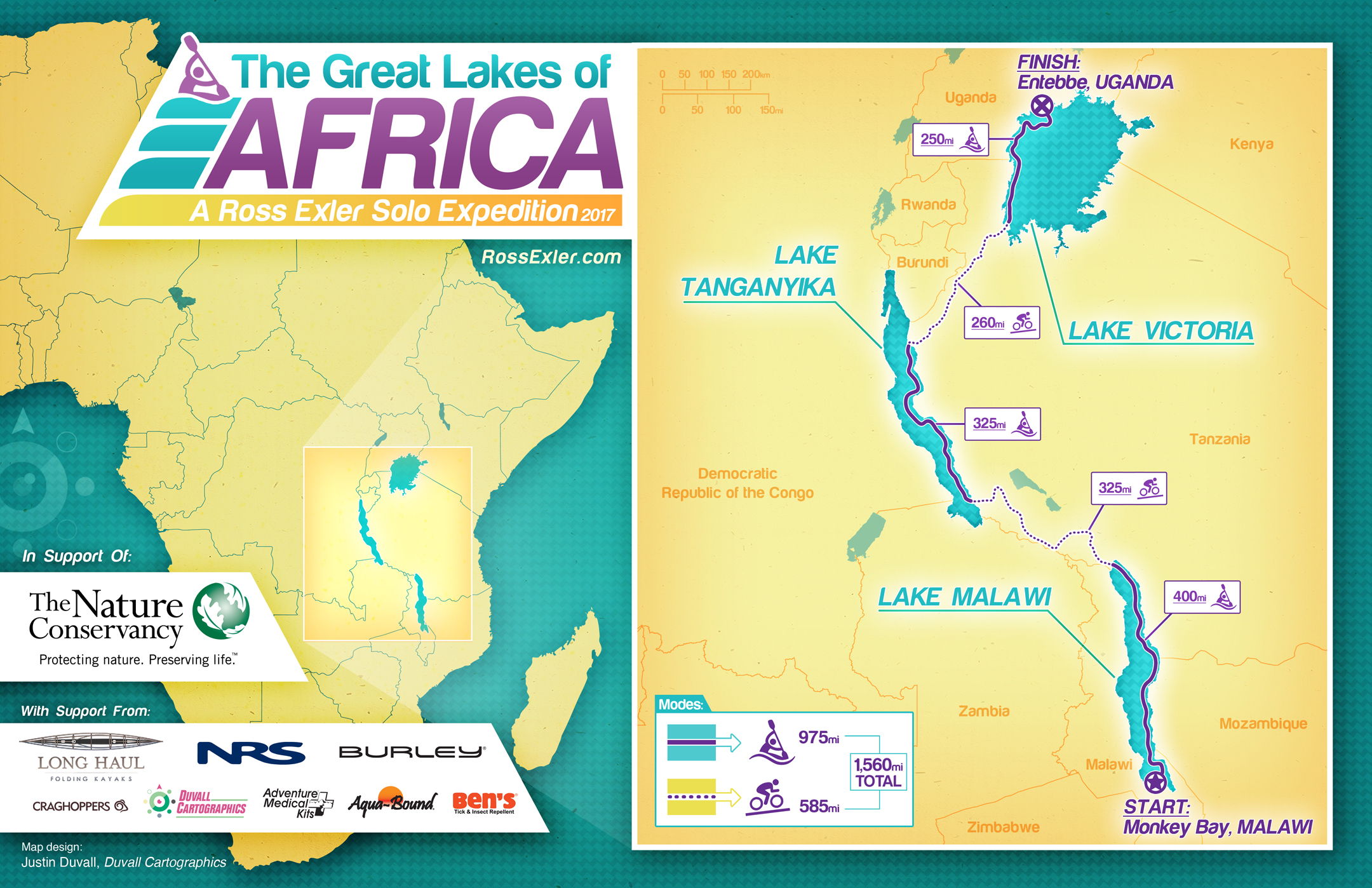

This January explorer Ross Exler sets out on his quest to paddle the African Great Lakes. He plans to paddle across the three largest: Lake Malawi, Lake Tanganyika, and Lake Victoria. The expedition will be the first unsupported, human powered, solo crossing of these lakes.

The total distance is about 1,000 miles of kayaking and 600 miles of biking from lake to lake through remote regions of Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Uganda. Exler will carry everything he needs, including a folding expedition kayak, folding bicycle, and folding bicycle trailer.

At press time, Exler was in Malawi waiting for a cyclone forming off the coast of Madagascar to pass before setting out. “The lake is looking massive and beautiful and I’m very excited to get going,” he says. The reason for his trip?

“I love Africa,” says Exler. “There are big animals, the landscapes are beautiful, the people are charming and endearing even when their living situation is very difficult. I go back there frequently, mostly recently for three months last winter to Botswana and Namibia in the Kalahiri. It’s a beautiful part of the world.”

He is also a man on a mission. He will be be working closely with The Nature Conservancy to promote awareness about the region and the work that it’s doing.

He writes, “The African Great Lakes region is extraordinarily important for vertebrate diversity, containing an estimated ten percent of the world’s species of fish. The lakes also contain approximately 25 percent of the world’s unfrozen freshwater. In addition to their ecological significance, the region’s fish and water are essential resources for the millions of people living along the shores of the lakes. Unfortunately, the lakes are under threat from invasive species, increases of sediment and nutrient inputs from deforestation and untreated sewage, over fishing, and the myriad impacts of poverty and war.”

No stranger to arduous journeys, Exler notes, “I’ve done a number of these large solo expeditions. I’ve got a background in biology and am drawn to these remote areas. To be by yourself and travel over a large area, that is the way to really experience it.” His most recent expedition was traveling 2,000 miles of the 4,000-mile-long Amazon River through Peru, Columbia, and Brazil for four months on a motorized canoe.

For this expedition, Exler needed a real boat plus a way to get it from lake to lake over roads. He reached out to Mark Eckhart at Long Haul Folding Kayaks, a low-key kayak company in Cedaredge, Colo. “Mark Eckhart was very enthusiastic and very helpful,” says Exler who refers to the kayak as a very high quality but artisanal project. The kayaks are made of wood frame components of ash hardwood and birch laminate with a rugged deck fabric of either cotton or acrylic. The company’s mission is to provide a safe and reliable way or reaching the most remote locations in the world. In the fall Exler went out to Colorado to pick up the kayak from Eckhart.

“It’s important too that he cares about how it goes for me and takes a lot of pride in his product,” he says.

Long Haul built the boat around a rugged, collapsible Burley bike trailer to make sure it fit inside the boat and made a custom skin to accommodate the bike. Exler will pack the boat up and put in on the trailer, and will bike the couple of hundred miles to the next lake.

“At night, I will wilderness camp or stay in small villages, relying on the kindness of local people – a reliance that has been rewarded time and again by good natured people in remote areas of the world. It is my hope to document the trip in a way that can bring you along to witness the splendor of this incredible place, and maybe to see some hippos and crocodiles from a safe distance.”

The itinerary is a starting point on the south end of Lake Malawi, at Monkey Bay, go through a portion of Mozambique and Tanzania, for 400 miles, then he will bike up and over to the Lake Tanganyika for 325 miles, then paddle up to Kigoma in Tanzania, or the vast majority of the lake. The lake ends in Burundi, but it has become a dangerous country, unacceptably dangerous. Then he will bike to the southwest corner of Lake Victoria, and paddle up to the northern end and finish in Entebbe, Uganda for 250 miles. Exler plans to take three months to complete the expedition and hopes to end the journey in March.

Exler is an accomplished photographer and story teller so look forward to stunning photos and finely spun stories.

To follow, www.RossExler.com

Cool Facts About Winter Seabirds

By Tamsin Venn

One reason to go kayaking in the Northeast now is to see winter seabirds. Recently I took a trip with Mass Audubon experts to find and identify these winter visitors around the rocky tip of Cape Ann, Mass. We went via heated vans, but I plan to return by kayak now I know what to look for.

Cape Ann’s exposed granite shores with crashing waves, plus protected harbors, seaside ponds, and sand beaches provide good habitat and viewing for these hardy seabirds.

Here is a list of the birds we saw and those you can expect to see out offshore now.

1) Red-breasted Merganser. Identifiable by the Mohawk haircut and narrow, red bill. The females have a rusty head. The narrow, serrated bill enables this diving duck to stab at fish and hold it firm in its bill or else grind crustaceans.

2) Common Eider. Eiders float in big rafts of dark brown females and distinct males with black bellies and white backs. They are the biggest sea duck of all and so easy to pick out from the buffleheads. If you’re really lucky, you might see a King Eider.

3) The Bufflehead a.k.a. “marshmallow head” is aptly named, for its large white round head and how it pops up on the water. One of the smallest and endearing ducks, it dines on mollusks and clams and swallows pebbles to help grind them up.

4) Three types of scoters. Close to shore you will see the Black and White-winged Scoter. It is rare to see the Surf Scoter which feeds farther out to sea. The key to IDing scoters is in the dabs of white on the cheeks.

5) The Double-crested Cormorant sprouts white feathers in the winter, but otherwise does not change dramatically from summer plumage. Fun detail, it sprouts two horn-like tufts at the top of its head in spring breeding season. It is easy to find by the orange bill and low stance in the water.

6) One of the biggest delights to see is the multi-colored, sea hardy Harlequin Duck, Latin name Histrionicus histrionicus. It is one of three rapid obligates in the world. That means it needs rushing water to feed so you often see them on rapidly flowing freshwater streams in summer. Along shore, they like the really rocky spots and can handle the strong water. Crashing waves break over them and they just sit there unperturbed.

7) Rarer to spot is the Long-tailed Duck, a striking bird with black and white markings; Horned Grebe; Lesser Scaup whose head may be nestled into its feathers and hard to ID because head shape is how you distinguish a Greater from a Lesser Scaup. Also, Hooded Merganser, Common Merganser, Ring-necked Duck, American Coot, Northern Pintail.

8) Scuttling along the rocks and seaweed you’ll find the Purple Sandpiper, so named for its slight purplish gloss. It’s the only sandpiper that sticks around in winter and is found mostly only on wave-washed rocks vs. sandy beaches or mudflats.

9) Shift your gaze out to sea and you might spot a Northern Gannett patrolling high above the water, steadily, floppily, winging by with its large wingspan and black wing tips. It’s common on open ocean, rare on land.

10) And you’re bound to see Herring, Great Black-backed, Ring-billed, and Bonaparte’s Gulls and of course the delightful Loons in their winter plumage.

11) If in doubt about the ID, check out the range maps in your guidebook and the blue bands for winter habitat. Happy winter paddling and bird watching!

Why Knot Go Fishing at Little Harbor Boathouse?

In late May, I head over to the Little Harbor Boathouse in Marblehead, Mass., to take part in a Guided Hobie Kayak Fishing Excursion. It would be a three-hour fishing program with use of a Hobie Kayak, fishing gear, and know-how from three very friendly and experienced guides: Jesse Minoski, Joe Gugino (see above photo on left), and Mike Marquis.

In late May, I head over to the Little Harbor Boathouse in Marblehead, Mass., to take part in a Guided Hobie Kayak Fishing Excursion. It would be a three-hour fishing program with use of a Hobie Kayak, fishing gear, and know-how from three very friendly and experienced guides: Jesse Minoski, Joe Gugino (see above photo on left), and Mike Marquis.

Our prey? The striped bass which had recently moved north from their southern vacations to spend the long summer feeding in New England waters. May and June is prime fishing season for this species.

The rocky shoreline around Marblehead is ideal striped bass territory, Hobie Team member Minoski says (he took the photo), and the Little Harbor Boathouse’s “hidden gem” location means you don’t have to go more than a half mile from the launch to fish and you duck out of the wind behind Crowninshield and Gerry’s Islands.

Maryellen Auger, owner of Little Harbor Boathouse, has a Hobie Revolution 11 waiting for me. It’s an ideal boat size for women, she notes. Sleek and lively, the Revolution uses a pedal system to propel forward (a paddle is attached by bungee chord on the side if you need it). The kayak comes in three lengths, 11, 13 and 16 feet, increasing in speed with the hull length. Conveniences include a molded-in rod holder, multiple hatches, lots of on-deck storage, and a “hyper adjustable” Vantage CT seat with webbing, that is so comfortable you could sit out there all day and cast a line. The seat sits off the floor and keeps you dry and is removable to turn into a beach chair.

I “power-pedal” my way out through Little Harbor behind Crowninshield and catch up with six eager clients and three helpful guides.

A couple of the clients catch fish on the dropping tide and release them. I’m not so lucky, but I can tell you how wonderful it is to sit out on the ocean in a comfy seat on a fresh spring day, casting a line, enjoying the beautiful surroundings, camaraderie, and communing with a species that obviously knows the most of any of us about the water dynamics and food below. All and all, I had a very good time and highly recommend it, especially for someone new to kayak angling such as myself.

Little Harbor Boathouse will hold two more Hobie First Cast Kayak Fishing Meetups this season. The dates are: Saturday, June 17, 8:30-11:30 (good Father’s Day outing) and Sunday, June 25, 10 a.m.-1 p.m.

Details and 24/7 on-line reservation to participate in Hobie First Cast Guided Kayak Fishing Excursions, Private Guides, and Hobie hands-free Kayak rentals visit:

http://littleharborboathouse.com/kayak-fishing/events

For ongoing fishing guiding service out of Little Harbor Boathouse – the blues come out in July – with 2017 Hobie Fishing Team Members Joe Gugino and Jesse Minoski: www.whyknotfishing.com

– Tamsin Venn