It has been said that in the Northeast, you can experience five seasons in the space of an hour: spring, summer, fall, winter, and biblical. That was certainly the case this past weekend (April 5-6) when we had rain, blizzard whiteout, dense fog, sleet, frozen rain, high winds, and warm sunny conditions all within 24, if not a single hour.

This is the shoulder season, in which we have to dress for water temperatures that are still well below the cold-water shock level, while risking heat stroke as the temperature in the drysuit rises to something around sauna levels. Red maple buds are returning to the trees; the sociable rafts of loons that visit our coast are abandoning their winter congregations and heading back to their long summer solitudes and the travail of chick-rearing; red buds on the maples signal sugaring time; and we are already pulling ticks off the dog.

Soon deep spring will be here, with its clouds of black flies, and summer with its suffocating plethora of biting, sucking, and stinging insect life. Here in our home port of Ipswich, Mass., when the vicious greenheads come out in July and the worst of the black fly infestation farther north and west is over, my thoughts again to the clear and abundant waters of the Adirondacks.

Ever since a childhood camp experience on the shore of Lake George, I have had a special feeling for the lakes and rivers of northern New York state. I have paddled, puddled, skated on, skied over, swum in, and hiked along the lakes, rivers, and creeks that nourish and drain the area. In 1974, I hiked, rafted, and kayaked the length of the Hudson River from its highest source, Lake Tear in the Clouds, on the shoulder of Tahawus, the Cloud Splitter (rather mundanely known by its official moniker of Mt. Marcy), along Opalescent Creek, all the way from the mountains to the sea, where its waters mix with and disappear into the Atlantic; but its bed continues to the edge of the continental shelf as the mighty Hudson Canyon.

On the other side of Tahawus from Lake Tear, Johns Brook rushes down into Keene Valley, at one point, three miles from the trailhead, forming one of the great swimming holes of the Adirondacks, rushing over smooth, potholed rock slabs in a series of slides, basins, and deep pools surrounded by plenty of sun-warmed stone perfect for alternately baking and quick cooling on a hot summer afternoon with the complimentary scents of dusty fir-scented forest and mountain water freshening the nose.

Keene Valley has a place in my family history, as well, for it was here that my many times-great grandfather (my namesake) settled after fleeing the armies of British and native Americans heading south under Burgoyne. My not-so-many times great-grandfather wrote down this bit of family lore many years later, as well as recounting his own experience of being chained to a tree with a supply of a few days food while his father surveyed the surrounding forests. I have, myself, walked the same trails and drunk from the same streams and even paddled where great-great-great-great-great Grandpa did, for these are the headwaters of the Hudson, and they are in places nearly as pristine as they were in his day.

Almost pristine implies a certain amount of development, and there is plenty enough of that in the Adirondack Park. This incredibly complex patchwork of state and private land constitutes one of the oldest and largest parks in the country. Development has gone on with few restrictions in the private portions of the park. Wealthy magnates in the 19th century built vast private estates as part of their own commercial interests, including a number of dams that now dot the region; this has actually been a boon to paddlers, as it means there are many dozens of miles of flatwater paddling on lakes that once were rivers.

About the time the aforementioned David Ward was growing up in the Adirondacks (in the 1820s and 30s), another young man was also maturing in what was still the relatively wild northeast, developing a love for “roughing it” that would stay with him throughout his life. He would later become one of the most beguiling of the siren calls tempting the public into the glorious Adirondacks.

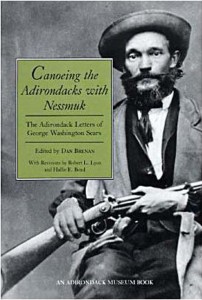

Everyone who remembers with delight the traditional ways of the woods, whose nostrils tingle with the smell of canvas tents and Old Woodsman bug dope, who remember the rough but warm texture of wet wool redolent of wood smoke knows of George Washington Sears, writing as “Nessmuk,” and his book Woodcraft and Camping, first printed in 1886 and still in print nearly a century later, one of the first handbooks of the wild to come out for an audience personally separated from wilderness life, but longing for the experience as the primeval forest became more and more remote from daily experience. (If you are interested in reading this wonderful old book, you can access a facsimile of the original and download it for free from the website for the Gutenburg Project’s website: www.gutenberg.org/files/34607/34607-h/34607-h.htm.) Filled with all the reader would need to know about camping, hunting, fishing, camp cookery, and canoeing. In all, but most notably in the case of paddling, he was an early proponent of traveling as light as possible, a philosophy that has become easier to hold to in this day of super light materials. Why Nessmuk became an apostle of camping with extreme simplicity in the golden age of the Adirondack guide boat, beautifully handcrafted but weighing in far closer to 100 pounds than the incredibly lightweight 10-12 pound canoes he used, is another story.

Fortunately for posterity, Sears chronicled his adventures in the Adirondacks in a series of letters to Forest and Stream, letters which have been collected and reprinted in one volume, available in many bookstores and on the web:

Canoeing the Adirondacks with Nessmuck

Canoeing the Adirondacks with Nessmuck

Edited by Dan Brenan, with revisions

by Robert L. Lyon and Hallie E. Bond

Format: Paperback,177 pages

Publisher: Syracuse University Press

Publish Date: March 1993

ISBN-13: 9780815625940

ISBN-10: 0815625944

Ret: $12.24 (walmart.com)

This little volume is a must read for anyone who wants to know more about paddling in the Adirondacks. One often thinks that stories about travelling in the wild from the 19th century, especially about areas that have been built up

Sears was not a large man, nor was he particularly healthy. Unlike the common image of the outdoorsman as a Paul Bunyon or Dan’l Boone, larger than life, eating a stack of pancakes ten feet tall, Sears stood just a few inches over five feet and weighed only 110 pounds. Also, by the time he was exploring the Adirondacks, he was experiencing health problems from recurring malaria and possibly tuberculosis picked up during an adventurous life that included a trip as a sperm whaler, long treks through the eastern wilderness, and even a journey to Brazil and up the Amazon to explore the possibility of making a fortune in the rubber industry.

So when Sears came to the Adirondacks, which were characterized by many portages, some exceeding ten miles, he had planned to travel as lightly as possible, not merely because he did not want to burden himself with a guide. (Sears was too poor to pay the $2.50 daily wage of a guide, and preferred travelling alone.) He was an old man by the standards of the age, weakened by disease, and he simply couldn’t carry heavy gear around. So he began a search for the lightest craft he could find. Working with boatbuilder J.H. Rushton, he paddled a series of cedar, clinker-built, increasingly tiny craft that culminated in the Rushton, an incredible eight-and-a-half feet long, 23 inches broad, with a depth of eight inches and weighing just one ounce under ten pounds. Sears only used this craft in protected waters in Florida. The last Rushton boat he paddled in the Adirondacks, the Sairy Gamp, was not much bigger, with dimensions of nine feet by 26 inches, six inches deep, and ten-and-a-half pounds.

Sears’ descriptions of his travels in the light boats caused a rush of orders for similar craft. Rushton complained, “Every damned fool who weighs less than 300 thinks he can use such a canoe too. I get letters asking if the Bucktail (slightly larger than the Sairy) will carry two good-sized men and camp duffel and be steady enough to stand up in and shoot out of.”

Even back in the 1880s the Adirondacks had lost their wildness in many areas. During Sears’ paddling summer of 1881, he travelled down the Fulton chain of lakes, portaging 3/4 of a mile from Fifth to Sixth lake, where the influence of a new dam was seen. Sears wrote,”The shoreline of trees stood dead and dying, while the smell of decaying vegetable matter was sickening. Last season, Sixth Lake was a wild, gamy place, and the best of the chain for floating. Its glory has departed…The present season finds the forest of balsam, spruce, and hemlock converted into a dismal swamp of dying trees, foul, discolored waters, and fouler smells.”

Despite his occasional despair at the despoilation of the wilderness, Nessmuk’s book is a wonderful glimpse into a world of lusty woodsmen and guides, city dwellers and pulmonary sufferers seeking refreshment in the wild, colorful backwoods characters, and glorious fishing and hunting. I strongly recommend this book.

Testing The Waters

Atlantic Coastal Kayaker blog site