By Tamsin Venn Photos by David Eden and Tamsin Venn

We arrived at this year’s Lake of October, Lake Umbagog (or Umbagog Lake — both placements are correct), before peak foliage season. The green-tinged ridges around the lake were smudged in orange and red, but the scarlet and yellow flames of maple and birch that line the stony shore had yet to light up this last week in September, possibly because of a warmer than normal summer and early autumn. (See Why Leaves Change Color).

As compensation, we had warm air and water temps, very welcome this far north at September’s end and a marked contrast to our shivery trip last year (ACK Vol. 29 #8, Nov-Dec 2020).

Um-BAY-gog (an Abenaki word for “clear water” or “shallow water”) is just 40 miles south of the Canadian border in Errol, N.H., in the Great North Woods. It’s the most downstream of the lakes in the Rangeley chain.

Originally, it was a series of three shallow lakes connected by marshes and swamps, but Errol Dam flooded the area in 1853 to form the lake here today. It is fed by the Magalloway, Rapid, and Dead Cambridge Rivers, and is the source of the Androscoggin River.

The lake is 10.4 miles long running north to south and 1.9 miles maximum width, with 50 miles of shoreline, an average 15-foot depth, and is mostly surrounded by dense forest, protected by several entities that have sought to convert lumber company tracts into wildlife protection area. Most development is on the lake’s southeast shore.

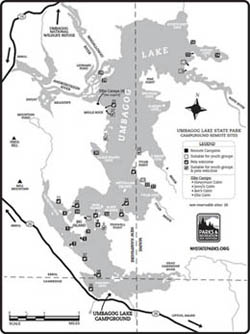

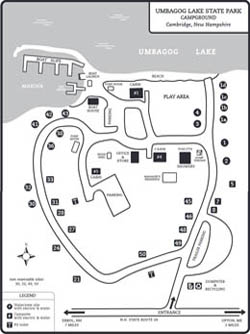

The Umbagog State Park campground provides good access. Located at the southern end, it has 27 campsites with electric, water, and hot showers; plus more than 30 remote campsites and four remote cabins (Ellis Camps) in isolated locations around the lake accessible only by boat. (You can park your car at the campground while you are away.) Most of the surrounding acreage beyond the shoreline is held by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). The area is undeveloped and wildlife abundant.

With a nudge from subscriber Paul Foster-Moore, we all planned to camp at a remote campsite at the lake’s north end. His crew wisely bailed when they heard the weather report — heavy rain — and for once the weather authorities were spot on.

Thanks to Foster-Moore, we reserved sites 13 and 18, at the north end of the lake (no dogs allowed; other sites do allow dogs). It is about a 7.5-mile paddle from the main campground.

You can also reach this area by launching in Errol, N.H., by the dam, paddling the Androscoggin, into the lake, cross it, go north, and land near the mouth of the Rapid River, which is known for its class III-IV whitewater. This river flows out of Lower Richardson Lake in the Rangeley Lakes in Maine. We were excited to explore this part of the lake and check out Sunday Cove. But iffy weather kept us anchored at the campground on the south end of the lake just off Route 26.

What a difference a year makes. As opposed to last pandemic fall, the place was hopping. Two White Mountain School groups launched on camping trips to Great Island. How their leaders take a possibly green group of teenagers off into the wilderness deserve a trophy engraved, “Kids, idle without social media on a remote island, four days, wind and rain included.” The girls missed most of the bad weather, but the boys, starting a couple of days later, set off just before they were deluged by pouring rain.

But what a great experience. I imagine the students returning to Umbagog 20 years from now to paddle and camp, the foundation laid. (“Or never go camping again,” grumped David.)

Also, something not evident last fall, the brisk business of campers being ferried out to the remote sites by pontoon boat, with gear, firewood, and canoes/paddleboards/kayaks, a regular service the campground provides for a fee. Stays are anywhere from two days to two weeks, Clem, the boat driver and general campground factotum, tells us. That allows boaters to get fairly far out to a site and then just paddle around without having to worry about schlepping all their gear.

Hmmm, there is something to this.

Many other camper/paddlers were hopping in kayaks and canoes and paddling here and there (the campground provides rentals). Also, motor boats launch from here. Non-campers can use the nearby public ramp.

One excellent narrative about life in the area near the northern end of the lake is Louise Dickinson Rich’s autobiographical book They Took to the Woods (1942). It is a witty account of the life she led in Forest Lodge, a remote family complex of cabins near Umbagog Lake in the 30s with her fly fishing fanatic (and guide) husband Ralph and young son, Rufus. The book made the best seller list and was selected for the Book of the Month Club and has been in print ever since. It may have appealed originally to an audience trying to make do during the depression. Her kerosene-lamp-lit cabin was on the Carry Road along the Rapid River, and cutting firewood was a major pastime.

Umbagog sits on the New Hampshire-Maine border, and it is very easy to paddle in and out of each state several times over a course of a day. Go for it.

Having abandoned the long-distance scramble to the top of the lake, we took to the south section. The lake has several “neighborhoods” worth exploring. The view from the campground is a broad lake stretching northward and intimidating looking if any wind is up, but on further exploration you find it has several areas to explore with islands and nooks and crannies to tuck into and wildlife to observe. Unfortunately, most of these features, including some largeish islands, are unnamed, so it is hard to describe where you have been. David says he can imagine an old New Hampshirite describing an island on Umbagog: “It’s thet one, ovah they-ah.”

The lake was extremely low in September, down eight feet by one count, due to a leak in the Androscoggin Dam and very low rainfall, according to the staff at the campground. (Despite record rains in southern New Hampshire, the North Country remains locked in a record drought, even after the downpours we were hit with.) My swim from the campground beach was a challenge, the swim area boundary cord lying on shore and slippery rocks of various sizes just beyond.

The pontoon service had been suspended to some sites and the sites closed because of boulders and other hazards exposed by the low water. Clem complained that he had had to take the engines in three times that season because of damage caused by collisions with the bottom. As ever, this is where kayaks come in. No problem landing for us.

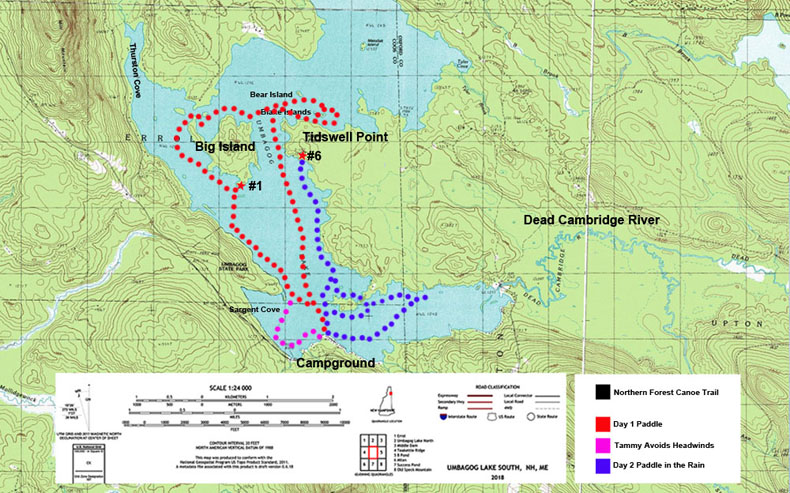

Day 1 — Thursday, Sept 23.

We lolled around camp in the morning, rare, rare, rare. We set off early afternoon, with an eye on sunset at 6 p.m. Weather called for south/southeast breeze at 5-10, which meant the breeze would push us north and we would be fighting it on the way back… yup.

We set out from from our tent site #41 (me) and beach (David) and headed east and north to a rock-strewn shore of dense cedar, birch, pine, and hemlock. When you land you have a better sense of the range of textures and smells. We rounded Tidswell Point, which opened up some of the most scenic paddling on the lake, with coves and islands all about. We circled around the Blake Islands (#32 on West Blake — great campsite, but no dogs). Millie was getting restive, and we paddled over to Bear Island to see if we could let her run a bit there. It’s private, so Sorry, Millie.

We then headed west across the lake to the north end of Big Island. The wind was getting much stronger, and we knew that the west shore of Big Island would be wind protected. We crossed over the northen end, past the Thurston Cove, and down the west side of Big. At its southern tip, we stopped to check out Site #1, leaving Millie tied in the boat (no dogs on Big Island) and take the last dry photo of the trip.

We headed southwest at a slight angle back to the western shore, using the strong south wind and resulting waves helping to ferry us as they came from our port bows. As the lake is shallow, long and exposed, and surrounded by hills which accelerate the winds, you get a robust fetch. Gusts made it worse, plus Millie, the dog, constantly standing up to check out the waves and acting as a backing sail that pushed me sideways to the wind. The chant of “Millie, sit down!” came periodically from me and David.

We are somewhat underboated in these conditions in our Hornbeck lightweight canoes, even though they are very seaworthy. The ease and light weight (17 and 24 pounds) are always hard to give up, but it would be an iffy crossing fully loaded. Once we reached the point on the northern end of Sargent Cove, I decided to take a less exposed route slightly into the cove, while David, with and extra three feet of boat, opted to bull straight ahead into the wind back to camp.

Distance/Time: 7.5 miles, three hours.

Weather: Partly sunny. Winds south 10 mph, rising to 15 with higher gusts.

Stops: Campsite #1 on Big Island.

Day 2 — Friday, Sept 24.

As predicted, the next day poured rain, although no thunderstorms, and we debated whether to take down camp and flee. First, however, we went out for a paddle. It was magical. The warm rain drenched us, the horizon disappeared in a blur, raindrops pocked the lake’s still surface, windless and quiet. The only downside was having to keep bailing. We stopped at the lovely Campsite #6 (two tent platforms, picnic table, firepit), bailed some more, and left. We could see very heavy smoke on Big Island, probably the White Mountain School boys trying to maintain a fire in the downpour.

The rain poured, then lightened, then poured, then the sun made a weak try, then the downpour again. It’s better to be in it, in my opinion, than watching the hourly reports and percentage of chance of rain and wondering whether to go paddling. Just go.

On our return, we were treated to the sight of not one, but four Bald Eagles. Our first sighting was an eagle in the distance crossing the lake. Our next view was much closer and far more interesting: A broad white tail flashing up from a beach on a narrow islet and escaping by flying low through the trees. We rounded the islet and there, on a muddy flat right in front of a house, hopped the same eagle, pecking at (presumably) the fresh water mussels that had been trapped on shore by the receding water. He took off again, stopped for a moment on a high branch to glare at us, then flew away across this larger “island.”

We continued navigating the group of what should have been islands, but were now a series of very shallow flats and peninsulas. Our frustration at not getting through was somewhat eased by the sight of two more eagles soaring high, but not far off. We decided to go all around the “island” and touch the narrow bar of muck that blocked us, to check for more birds sightings and so we could claim a circumnavigation. On the way, we passed either side of the islet where we had first seen the eagle. David saw a small group of Least Sandpipers running over a line of fractured rocks on the northern shore of the islet. We joined up again and headed east on the long inlet formed by the sunken bed of the Dead Cambridge River. Running into what should have been a channel, but was now a neck connecting the island and the mainland, we startled a flock of Mergansers, who fled rapidly at our approach. They seemed especially shy, probably because this is hunting country.

As we turned back towards the camp, we caught our favorite bird sighting of the day: an apparent tangle of branchlets on a high pine turned out to be a thoroughly wet eagle sitting high in a dead tree, its wing feathers drooping soaked from the rain, looking like a very ratty national symbol. Was it our mussel-eater from the other side? “Nope!” said David. Let’s up our eagle count to four!”

Distance/Time: Six miles, 2.5 miles.

Weather: Heavy rain. Calm to light southeast wind, rising as the cold front passed.

Stops: Campsite #6 on Tidswell Point.

Situated in the southern range of the boreal forests and the northern range of the deciduous forests, Umbagog is a transition zone providing homes to species of both habitats, says the USFWS brochure.

Umbagog is an eBird Hotspot (an online citizen-scientist site for posting bird sitings). The well-known viewing areas here are the backwaters along the Magalloway and Androscoggin Rivers and in coves and marshes at the lake’s north end.

During the course of two days here we saw Bald Eagle, Pileated Woodpecker (more interested in berries than pecking for insects), American Kestrel, Great Blue Heron, Common Loon, Belted Kingfisher, Common Merganser, American Black Duck, Double-crested Cormorant, Black-capped Chickadee, Blue Jay, Least Sandpiper, American Crow, and a number of unidentified ducks. We saw no osprey, which are common here, taking advantage of the lake’s many fish. They had probably already migrated south. The Bald Eagles stay year round if open water and carrion allow.

One needs to remember that starting in the 40s, no Bald Eagles lived here. They were totally absent in New Hampshire in the 1940s due to DDT but started making a comeback in 1989. “One male, released in New York in 1984, made his way to Umbagog Lake and in 1989 began nesting with a female eagle at Leonard Pond, at the north end of Umbagog Lake. This was the first bald eagle nest discovered in New Hampshire in 40 years, and it was built in the very same tree [white pine] that held the last successful nest in 1949.

Bald Eagles of the Umbagog Area

Throughout the 1980’s Massachusetts and New York released dozens of young, transplanted eagles into the wild (Martin, 2001). One male, released in New York in 1984, made his way to Umbagog Lake and in 1989 began nesting with a female eagle at Leonard Pond, at the north end of Umbagog Lake. This was the first bald eagle nest discovered in New Hampshire in 40 years, and it was built in the very same tree that held the last successful nest in 1949.

Initially, the eagles behaved as though they had young and biologists assumed there were one or more chicks in the nest. Then suddenly the behavior of the eagles changed, and it became clear that the chick(s) had not survived. Working quickly, biologists found a captive-raised chick to put in the nest. Placing a foster chick into a nest that already has a chick is not that uncommon. However, placing a foster chick into an empty nest was unusual and we anxiously awaited the results. The experiment worked and the eagles accepted and successfully raised the foster chick. During the next breeding season the adults fledged two young of their own.

The Leonard Pond territory has remained continuously active since 1989. Between1989 and 2001, the nest produced 16 young (including two foster chicks). The original banded female paired with several different males during that time. The original male of the pair died from suspected lead poisoning in 1994, and the female immediately paired with a second male. That second male disappeared after 1999 and the female paired with a new male. 2001 marks the last year that the original banded female (then 16 years old) was confirmed to have nested at Leonard Pond. In 2002, an unidentified pair of eagles occupied the Leonard Pond territory, but failed to lay any eggs. During 2003 through 2005, a new, unbanded pair occupied the territory but failed to successfully hatch any chicks. However, in 2006 the nest was successful and three healthy chicks were fledged.

Since the first eagle pair nested at Leonard Pond in 1989, two other nesting eagle territories have been established in the vicinity of Umbagog Lake. One of these, located east of the lake, has successfully fledged chicks each year since it was first observed in 2000. In 2005 a third eagle territory was established in Sweat Meadow, and in 2007 a nest was discovered in Rapid River.

Kate Maguire 7/1/2001, revised 11/2006.

Umbagog National Wildlife Refuge Northeast Region

Click for full-size image

Click for full-size image

Click for full-size image