After many years in the same family, one of our local boat stores changed hands this past spring. Fernald’s Marine sat on the edge of the Parker River, near Plum Island, Mass. Everyone drove by Fernald’s, because it was right on the main route to Newburyport. The store had large glass windows that resembled a 1950s garage so you could windowshop the inviting small craft such as canoes and day sailors as you drove by. Almost everyone bought their first canoe there, me included. Eventually kayaks showed up, inspiring all those passing to get on the water.

After many years in the same family, one of our local boat stores changed hands this past spring. Fernald’s Marine sat on the edge of the Parker River, near Plum Island, Mass. Everyone drove by Fernald’s, because it was right on the main route to Newburyport. The store had large glass windows that resembled a 1950s garage so you could windowshop the inviting small craft such as canoes and day sailors as you drove by. Almost everyone bought their first canoe there, me included. Eventually kayaks showed up, inspiring all those passing to get on the water.

This past April a wonderful family bought the place from the Fernalds who ran it for three generations. On a nice sunny, summer Sunday in June, Matt Yablonowski Northeast sales rep for Confluence, came for a couple of hours to let the locals try out kayaks. One bonus of having a family buy the place, is the purchase brought with it four strong, polite, cheerful, energetic teenagers and their friends. Matt got lots of help schlepping kayaks to the dock, then helping people get in, plenty of young, strong hands to hold the boats steady for the dock launch.

What is kayaking without some schlepping? What is the first question many of us ask when buying a new kayak? How much does it weigh? Maybe the trick to aging boomer kayakers are not the continually evolving gadgets that help us get the kayak on the roof of our cars, but borrowed teenagers. Kid Kayak Valet service.

Monthly Archives: June 2014

July/August 2014 – A Fantasy Paddle Through Ancient America

Sumer is icumen in,

Lhude sing, cuccu;

Groweth sed and bloweth med,

And springth the wode nu;

Sing, cuccu!

The sumer is icumen in at last, after a rather poor spring. Tammy and I went down to the beach at the end of the road late yesterday to de-tick in the frigid water after a ten-mile ramble in the woods and found the cars backed 30 deep still waiting to get in. the sand was so crowded that it was hard to find a place to drop our towels. Off the coast, stink-pots (a.k.a. motor boats) and the obnoxiously noisy and insanely driven personal watercraft careened back and forth. It’s that time of year again, when the peace of ocean, lake, and river is shattered by the endless roar of inadequately muffled motors, and the paddle enthusiast fears for his or her life as fleets of unseeing, unaware, and even intoxicated drivers take to the water.

Okay, so I am prejudiced against motor craft. This (with the sobriquet “stink-pot”) dates back to my childhood as a committed sailor. I could appreciate their usefulness as utility boats to service the needs of true sailors (travel to and from the yacht club where my sailing camp was, or towing to a race venue, for instance), but what kind of yahoo would choose a motor boat over a sail- or muscle-powered craft for recreational purposes?

Whenever the air is made hideous by the cacophony of a myriad of throbbing engines, my thoughts turn with longing to the times and places when I have been able to paddle for hours or days in the silence of nature, which is no silence at all, but is the sound of the wild without an engine within hearing,

I remember long paddles along rocky coasts with the wind whistling and surf crashing against the cliffs. A spring morning on the St. John River in Maine, with the forest wall echoing with birds calling so fervently their songs of passion and possession that the sounds of the river and our paddles in the water were completely drowned out. A mid-summer early morning on the Hudson in upstate New York, a long, forest-girdled deadwater, glassy in the still morning air, with the only sound the faint ripple of my kayak’s bow as it sliced cleanly through the still water, and the muffled plash of the paddle stroke. Winding through narrow mangrove alleys in Florida’s Everglades, hunting for alligators and gazing at the prehistoric, scaly beasts warming themselves on the occasional muddy bank, paddling under pendant epiphytes, their odd, spiky blossoms punctuating the solid greens with color. A tiny sound of clicking as a sandy bank, pocked with holes, explodes into hundreds of fiddler crabs saluting us with their over-sized claws as we drift past.

These memories, plus a taste for old tales of travel and how-to camping books of 1940 and earlier, always lead to romantic fantasies of what it would be like if North America could be returned to its state before the Euro-invasion starting in the 15th century. I won’t say a state of nature, because much of the area was actually managed by the locals, but the mark they made on the landscape was less obviously destructive than that which was to come.

I would, of course, not really want to paddle the forests of America in the 15th century. Lacking movies, smartphones, video games, and other electronic pastimes, the young men would amuse themselves with inter-tribal warfare, bringing home any prisoners to be adopted or excruciatingly done to death, depending on the day of the week or the general desire for some group entertainment.

I would, of course, not really want to paddle the forests of America in the 15th century. Lacking movies, smartphones, video games, and other electronic pastimes, the young men would amuse themselves with inter-tribal warfare, bringing home any prisoners to be adopted or excruciatingly done to death, depending on the day of the week or the general desire for some group entertainment.

I have often thought the ideal world for me would be pre-Euro America, with some modern conveniences, including doctors, a good supply of books, and a few convenient super markets in case I got tired of venison and succotash. One would need to have a modern forager’s knowledge, plus a plot of garden to grow corn, beans and squashes. Heck, since this is a fantasy, we’ll include carrots, potatoes, and a number of fruits and vegetables. The paddling, at least, would be fabulous.

Feeding oneself in this perfect world would not be much of a problem, as game abounded to a degree that we can hardly imagine. Lobsters the size of golden retrievers crawled about the inshore, although we would have to forgo lemons. Paddling them up from the tropics might be a logistical problem.

So, where to paddle? This is our dream voyage, after all. We could paddle south, with a long portage across Cape Cod, then along the coasts of Rhode Island and Connecticut, into the Harlem River. Crossing to the Hudson, we move north. We want to see the Great Lakes, so we have to decide on whether to go up the Mohawk or to continue north until we can cross over to Lakes George and Champlain, then down the Richelieu River into the St. Lawrence. On either track, we could hop over a few miles to wander around the Adirondack lakes for a few weeks, Of course, we could have gotten to the St. Lawrence with a long paddle Down East and around the Gaspé Peninsula. Lots of beautiful, pristine islands to camp on , and no worries about access. Up the St. Lawrence and spend a couple of years exploring the lakes, then south via the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico. From here, we turn east to travel down the Florida coast, gunkholing all the way through the waters described so feelingly by Robb White in How to Build a Tin Canoe. After some time revisiting the mangrove coast of the Everglades and the Keys, we move back north and west to take in the Texas beaches, continuing along the Gulf coast to Mexico and Central America, where we can visit the native civilizations in their fabulous, pre-Conquest glory. Remember, this is a fantasy journey, so we don’t have to worry about having our hearts ripped out to feed the Sky Gods, or having our skin end up as some priest’s pyjamas. The warrior classes in this world are more like Mardi Gras dance krewes: still gorgeously dressed, but not killing you on sight.

Surfeited with jungle and dishes cooked in chocolate, we turn north once more for the long paddle back to our hilltop wigwam in Ipswich and the end of our fantasy paddle.

May 2014

It has been said that in the Northeast, you can experience five seasons in the space of an hour: spring, summer, fall, winter, and biblical. That was certainly the case this past weekend (April 5-6) when we had rain, blizzard whiteout, dense fog, sleet, frozen rain, high winds, and warm sunny conditions all within 24, if not a single hour.

This is the shoulder season, in which we have to dress for water temperatures that are still well below the cold-water shock level, while risking heat stroke as the temperature in the drysuit rises to something around sauna levels. Red maple buds are returning to the trees; the sociable rafts of loons that visit our coast are abandoning their winter congregations and heading back to their long summer solitudes and the travail of chick-rearing; red buds on the maples signal sugaring time; and we are already pulling ticks off the dog.

Soon deep spring will be here, with its clouds of black flies, and summer with its suffocating plethora of biting, sucking, and stinging insect life. Here in our home port of Ipswich, Mass., when the vicious greenheads come out in July and the worst of the black fly infestation farther north and west is over, my thoughts again to the clear and abundant waters of the Adirondacks.

Ever since a childhood camp experience on the shore of Lake George, I have had a special feeling for the lakes and rivers of northern New York state. I have paddled, puddled, skated on, skied over, swum in, and hiked along the lakes, rivers, and creeks that nourish and drain the area. In 1974, I hiked, rafted, and kayaked the length of the Hudson River from its highest source, Lake Tear in the Clouds, on the shoulder of Tahawus, the Cloud Splitter (rather mundanely known by its official moniker of Mt. Marcy), along Opalescent Creek, all the way from the mountains to the sea, where its waters mix with and disappear into the Atlantic; but its bed continues to the edge of the continental shelf as the mighty Hudson Canyon.

On the other side of Tahawus from Lake Tear, Johns Brook rushes down into Keene Valley, at one point, three miles from the trailhead, forming one of the great swimming holes of the Adirondacks, rushing over smooth, potholed rock slabs in a series of slides, basins, and deep pools surrounded by plenty of sun-warmed stone perfect for alternately baking and quick cooling on a hot summer afternoon with the complimentary scents of dusty fir-scented forest and mountain water freshening the nose.

Keene Valley has a place in my family history, as well, for it was here that my many times-great grandfather (my namesake) settled after fleeing the armies of British and native Americans heading south under Burgoyne. My not-so-many times great-grandfather wrote down this bit of family lore many years later, as well as recounting his own experience of being chained to a tree with a supply of a few days food while his father surveyed the surrounding forests. I have, myself, walked the same trails and drunk from the same streams and even paddled where great-great-great-great-great Grandpa did, for these are the headwaters of the Hudson, and they are in places nearly as pristine as they were in his day.

Almost pristine implies a certain amount of development, and there is plenty enough of that in the Adirondack Park. This incredibly complex patchwork of state and private land constitutes one of the oldest and largest parks in the country. Development has gone on with few restrictions in the private portions of the park. Wealthy magnates in the 19th century built vast private estates as part of their own commercial interests, including a number of dams that now dot the region; this has actually been a boon to paddlers, as it means there are many dozens of miles of flatwater paddling on lakes that once were rivers.

About the time the aforementioned David Ward was growing up in the Adirondacks (in the 1820s and 30s), another young man was also maturing in what was still the relatively wild northeast, developing a love for “roughing it” that would stay with him throughout his life. He would later become one of the most beguiling of the siren calls tempting the public into the glorious Adirondacks.

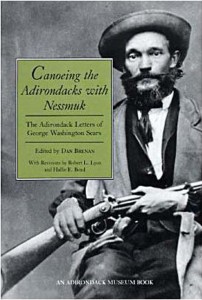

Everyone who remembers with delight the traditional ways of the woods, whose nostrils tingle with the smell of canvas tents and Old Woodsman bug dope, who remember the rough but warm texture of wet wool redolent of wood smoke knows of George Washington Sears, writing as “Nessmuk,” and his book Woodcraft and Camping, first printed in 1886 and still in print nearly a century later, one of the first handbooks of the wild to come out for an audience personally separated from wilderness life, but longing for the experience as the primeval forest became more and more remote from daily experience. (If you are interested in reading this wonderful old book, you can access a facsimile of the original and download it for free from the website for the Gutenburg Project’s website: www.gutenberg.org/files/34607/34607-h/34607-h.htm.) Filled with all the reader would need to know about camping, hunting, fishing, camp cookery, and canoeing. In all, but most notably in the case of paddling, he was an early proponent of traveling as light as possible, a philosophy that has become easier to hold to in this day of super light materials. Why Nessmuk became an apostle of camping with extreme simplicity in the golden age of the Adirondack guide boat, beautifully handcrafted but weighing in far closer to 100 pounds than the incredibly lightweight 10-12 pound canoes he used, is another story.

Fortunately for posterity, Sears chronicled his adventures in the Adirondacks in a series of letters to Forest and Stream, letters which have been collected and reprinted in one volume, available in many bookstores and on the web:

Canoeing the Adirondacks with Nessmuck

Canoeing the Adirondacks with Nessmuck

Edited by Dan Brenan, with revisions

by Robert L. Lyon and Hallie E. Bond

Format: Paperback,177 pages

Publisher: Syracuse University Press

Publish Date: March 1993

ISBN-13: 9780815625940

ISBN-10: 0815625944

Ret: $12.24 (walmart.com)

This little volume is a must read for anyone who wants to know more about paddling in the Adirondacks. One often thinks that stories about travelling in the wild from the 19th century, especially about areas that have been built up

Sears was not a large man, nor was he particularly healthy. Unlike the common image of the outdoorsman as a Paul Bunyon or Dan’l Boone, larger than life, eating a stack of pancakes ten feet tall, Sears stood just a few inches over five feet and weighed only 110 pounds. Also, by the time he was exploring the Adirondacks, he was experiencing health problems from recurring malaria and possibly tuberculosis picked up during an adventurous life that included a trip as a sperm whaler, long treks through the eastern wilderness, and even a journey to Brazil and up the Amazon to explore the possibility of making a fortune in the rubber industry.

So when Sears came to the Adirondacks, which were characterized by many portages, some exceeding ten miles, he had planned to travel as lightly as possible, not merely because he did not want to burden himself with a guide. (Sears was too poor to pay the $2.50 daily wage of a guide, and preferred travelling alone.) He was an old man by the standards of the age, weakened by disease, and he simply couldn’t carry heavy gear around. So he began a search for the lightest craft he could find. Working with boatbuilder J.H. Rushton, he paddled a series of cedar, clinker-built, increasingly tiny craft that culminated in the Rushton, an incredible eight-and-a-half feet long, 23 inches broad, with a depth of eight inches and weighing just one ounce under ten pounds. Sears only used this craft in protected waters in Florida. The last Rushton boat he paddled in the Adirondacks, the Sairy Gamp, was not much bigger, with dimensions of nine feet by 26 inches, six inches deep, and ten-and-a-half pounds.

Sears’ descriptions of his travels in the light boats caused a rush of orders for similar craft. Rushton complained, “Every damned fool who weighs less than 300 thinks he can use such a canoe too. I get letters asking if the Bucktail (slightly larger than the Sairy) will carry two good-sized men and camp duffel and be steady enough to stand up in and shoot out of.”

Even back in the 1880s the Adirondacks had lost their wildness in many areas. During Sears’ paddling summer of 1881, he travelled down the Fulton chain of lakes, portaging 3/4 of a mile from Fifth to Sixth lake, where the influence of a new dam was seen. Sears wrote,”The shoreline of trees stood dead and dying, while the smell of decaying vegetable matter was sickening. Last season, Sixth Lake was a wild, gamy place, and the best of the chain for floating. Its glory has departed…The present season finds the forest of balsam, spruce, and hemlock converted into a dismal swamp of dying trees, foul, discolored waters, and fouler smells.”

Despite his occasional despair at the despoilation of the wilderness, Nessmuk’s book is a wonderful glimpse into a world of lusty woodsmen and guides, city dwellers and pulmonary sufferers seeking refreshment in the wild, colorful backwoods characters, and glorious fishing and hunting. I strongly recommend this book.